Section Menu

Navigating Borderized Mexico

Mapping the Machines and Counter-Machines of Borderized Mexico

Legal Bureaucracies and the Law without Letter

Spectrums of Politicization

Caring for Migrant Subjectivities

Theological Counter-Machines: between Indifference and Activism

Caudillismo as an Organizing Logic of Responses to Migration

Migrant Zapatismo

Coda: Empty Chairs

Navigating Borderized Mexico

On 7 July 2014, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto and Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina held a press conference at an immigration checkpoint in Playas de Catazaja, where together they announced Mexico’s Programa Frontera Sur, more commonly known as Plan Frontera Sur or the Southern Border Plan. The announcement did not correspond with any official change in written law, but it heralded a shift in the official state discourse on Central American migration through or to Mexico, as well as a shift in the practices of government agents responding to migrants and migration. In this sense, we might consider it law without letter—a policy with the valence of legality and with concrete effects, but without any written legislation.

In his press conference and in ensuing statements, President Peña Nieto claimed that Plan Frontera Sur is meant to protect the rights of undocumented migrants in Mexico, and his pledges have included giving migrants temporary visas, improving conditions in migrant shelters and detention centers, and offering migrants medical care. The effects of the Plan, though, have been markedly different than these stated aims. Since July 2014, the forces patrolling the Mexico-Guatemala border have increased, involving immigration agents, local and federal police forces, and the Mexican military, and been given sophisticated surveillance equipment, and the number of checkpoints near the southern border has expanded. The migrants who are detained or deported at these checkpoints then face a legal system at turns bureaucratically labyrinthine and overtly oppressive, which they must navigate in their attempts to prevent unfounded accusations and detention or to gain even temporary visas.

Useful in understanding how the letterless, permeable law of Plan Frontera Sur creates these conditions is the notion of borderization, a term we borrow from Alejandro Grimson. In our context, we use it to refer to the extension of the technologies of control that traditionally reside at physical borders across a nation through the proliferation of these technologies and their accompanying social relations and formal and civilian policing practices. This borderization, in theory and in Mexico, produces the border both everywhere and nowhere, transforming all of Mexico into a “vertical border.” Borderization, or the process of borderizing, is precisely the mechanism through which Plan Frontera Sur controls and polices migrants not just at the southern border or in the process of illegalized activities, but across the national territories of Mexico and Central America and in all contexts of life.

The result of this mode of enforcement of Plan Frontera Sur and its borderization effect, perhaps unsurprisingly, has been an unprecedented number of deportations from and detentions in Mexico and an increasingly dangerous, fugitive and precarious life, to use a key term from Judith Butler, for illegalized Central American migrants in the country. In the wake of these widespread conditions, and of the expanding neoliberalism of the Mexican government more generally, which has moved the responsibility for care and public services from the state to private actors, the work of the networks of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), political movements, and human rights advocacy groups in Mexico that aim to improve the conditions of migrants has taken on increasing urgency and importance.

This section aims to track the work, organization and motivations of these groups and actors, which, following Rossana Reguillo, we refer to as “counter-machines,” and the challenges they face navigating the machinery of the Mexican state and legal system. Though counter-machines may be located in state institutions, the “phantasmagoric and radically disciplinary power of the [state] machine” makes it so that they are more effectively and pervasively present through the actions of various citizens and NGOs, which offer the “fragile, intermittent, expressive, and fragmented devices society deploys to resist, make visible, or subtract power” in the face (or facelessness) of the oppressive state response to migration. As such, many of the counter-machines we discuss in this section are paragovernmental, or, in some cases, overtly opposed to the Mexican government, but we hope, too, to provide a sense of the large, complicated network of groups both governmental and otherwise that engage in the work of managing the lives of migrants in a borderized Mexico.

Indeed, the management of life and conceptions of how to protect and foster it are axiomatic to the functioning of these networks and to the discussions in this section. Mexico, like many modern state regimes, can be understood as acting on both citizens and migrants through Foucaultian biopolitics: Mexican governmental institutions are in the business of managing the lives of those within their borders, asserting “a power to foster life or disallow it to the point of death.” The position of migrants in Mexico in particular can be thought of in these terms, as the state constantly regulates their routes, positions, freedom to move, access to public services, and legal identities, while it also clearly imposes burdens on migrants that let them die. In the face of this biopolitical functionality of the state and of Plan Frontera Sur especially, many of the counter-machines in Mexico engage in alternate modes of managing and valuing the lives of migrants. As we discuss in some subsections, the counter-machines we came into contact with have varied conceptions of the work that they do and their relation to the machinery of the Mexican government and Plan Frontera Sur: some are motivated by a religious understanding of the dignity of life; some focus on providing care for migrants, while others mobilize into political movements; some work with individual migrants; and some look outwards to the generalized neoliberal control over life and death in a borderized Mexico.

Implicit in all of these modes of operation, though, is the sense that the work of the actors in these networks is fundamentally bounded to different, resistant ways of relating to and managing the lives of people simultaneously attempting to escape the biopolitical violence of state machinery and fundamentally bound up in it. Alternate understandings of life and the care, mobilization, and management of it might, ultimately, be the most urgent task of counter-machines at this moment in Mexico.

Mapping the Machines and Counter-Machines of Borderized Mexico

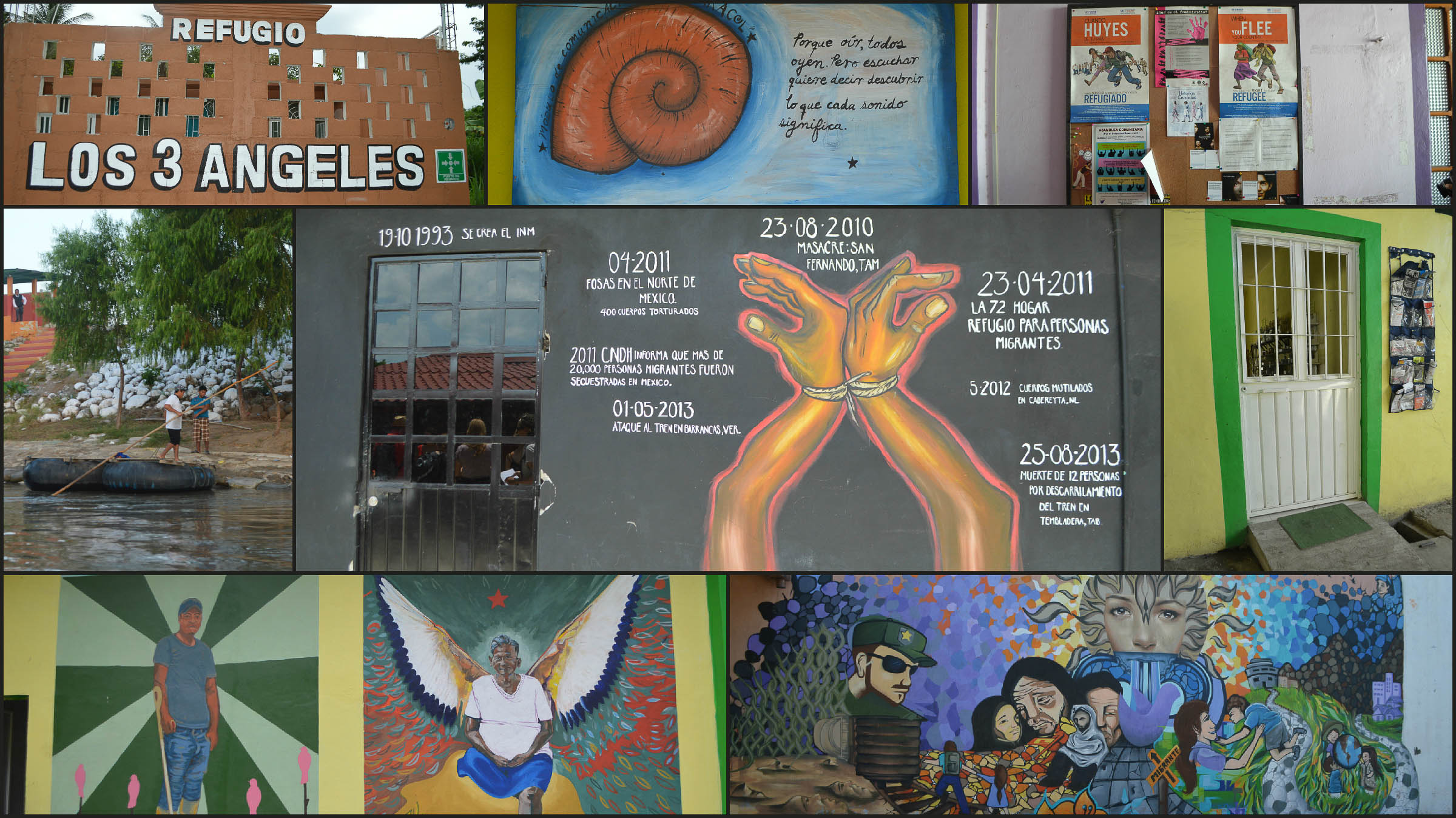

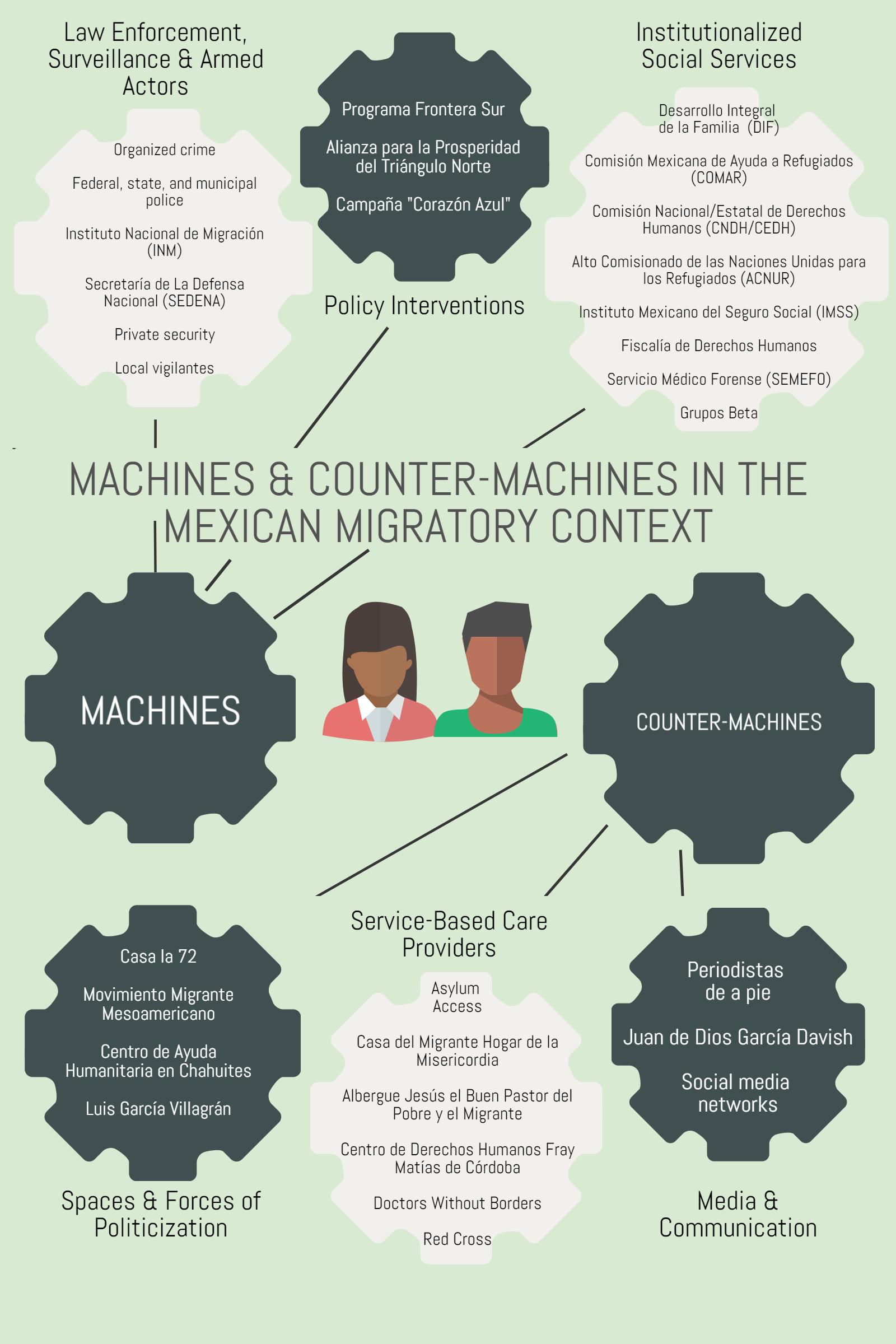

During our time tracing migratory routes along the southern border of Mexico, we encountered a diverse set of actors and institutions working in relation to migrants with an even more diverse set of relations to one another. While some of these actors and institutions conspire to maintain the current imbalance of power that reduces migrant bodies to human refuse or opportunities for profit, others aim in various ways to aid or act politically for and with migrants and other displaced persons. The above image is a preliminary attempt to visually make sense of the tangle of actors and institutions present in the Mexican migratory context through the logic of machines and counter-machines discussed in the previous subsection.

Among the machine-like institutions at work in relation to migration in Mexico, we include the subcategories “Law Enforcement, Surveillance & Armed Actors,” “Policy Interventions,” and “Institutionalized Social Services.” Each of these machines, in spite of sometimes-good intentions, participates in the subhumanization of the migrant to varying degrees and in the oppressive biopolitical management of migrants. While the physical and sexual violences enacted on migrant bodies by organized criminals and local vigilantes may be the most obvious example of this subhumanization, we can also see it manifested in the hyper-surveillance of the migrant traversing the “vertical border” or in the lack of external recourse for migrants navigating governmental bureaucracies. In our discussion with Gerardo Espinoza of Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías de Córdóva, for example, we learned that migrants applying for refugee status through the Comisión de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR) are forced to report any suspected oversights in or mishandlings of their cases to the very same caseworkers that originally processed them, rather than to an outside ombudsperson.

Interview with Gerardo Espinoza Santos of Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías de Córdóva, Tapachula.

As far as “Policy Interventions” in borderized Mexico are concerned, Plan Frontera Sur has become the most infamous and iconic. Plan Alianza para la Prosperidad del Triángulo Norte and the Campaña “Corazón Azul” have also led to the hyper-regulation and surveillance of migrant bodies, though, under the auspices of transnational political and economic alliances and the management of the troubling uptick in human trafficking, respectively. Plan Alianza para la Prosperidad, which was envisioned in response to the “crisis” of unaccompanied child migrants in 2014, purports to improve the economic and social conditions in the countries of origin of migrants, with the aim of quelling emigration. Migrants’ rights activists fear, however, that this is just an attempt to expand the vertical border and its policing practices beyond Mexico into Central America. Similarly, the Campaña “Corazón Azul” was devised as an effort to stem the booming human trafficking industry, but in practice targets vulnerable migrant women and sexual minorities, whose unjust detainments the state can flaunt as proof of a supposed crackdown on trafficking. To counteract the false accusations of human trafficking lodged against predominantly Central American women, human rights defenders like Luis García Villagrán have provided pro-bono legal aid and drawn attention to the problem through press strategies and political actions. Those enforcing these laws, like those who have militarized Mexico, and particularly the areas around the border, under the auspices of Plan Frontera Sur, exploit “the gap between the law as it is written and the law as it is embodied” at the expense of migrants.

Just as the machines that act on migrant bodies are not monolithic, there is a wide variety of types of counter-machines at work in borderized Mexico. We have divided these counter-machines into the preliminary categories of “Spaces & Forces of Politicization,” “Service-Based Care Providers,” and “Media & Communication.” These categories have allowed us to conceptualize and analyze counter-machines that defy the traditional terminology of “actors” and “institutions.” For example, this more open interpretation of the counter-machine provides room for an exploration of the role of social media in drawing attention to human rights abuses or providing information about migratory routes and services along those routes to migrants. Within the larger framework of counter-machines, we also make the distinction between “Spaces & Forces of Politicization” and “Service-Based Care Providers” to differentiate between projects with a primary aim toward political identity formation and those that seek primarily to alleviate the individual migrant struggle (the latter often employing the rhetoric of charity and compassion, as we discuss later).

Though this map does not aim to be and perhaps by nature cannot be a complete guide to the actors and institutions involved in migration in Mexico today, we hope that it begins to provide a sense both of who we came into contact with on our trip and of the complicated, overlapping network of forces that migrants must navigate and that, in some cases, seek to help them make that navigation.

Legal Bureaucracies and the Law without Letter

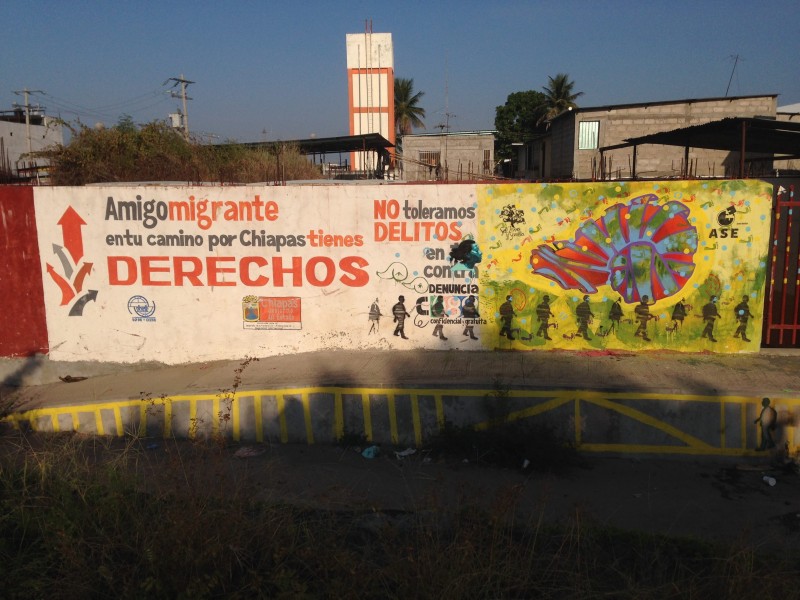

When migrants cross a certain part of the Suchiate River, which separates Guatemala and Mexico and which serves as a point of entry for Central Americans heading north, they are faced on their way over with a graffitied sign sponsored by the Secretary for the Development of the Southern Border and the Link for International Cooperation, reading: “Migrant friend, in your journey through Chiapas you have rights.” Invocations of legal rights and encouragements that migrants turn to the law are pervasive further into Mexico, as well. Posters and pamphlets meant to inform migrants about their legal options in the country populate shelters and hostels; a representative from the Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos Oficina Foránea came to offer legal assistance and information to the migrants at during our visit to the Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes shelter; and towering over the central square in Tapachula is a billboard paid for by the Chiapas government urging migrant readers to file legal claims to protect them against abuses.

Indeed, as a number of migrants and human rights workers articulate, the legal system can be a resource that migrants turn to both for retribution for crimes that they are the victims of and, perhaps more importantly, in order to facilitate their existence in or travels through Mexico. A few migrants at the shelters we visited were in the process of pursuing legal charges in response to assaults, and they explained their motivation for undergoing the lengthy and arduous process of filing a claim, recreating the crime for legal officials, and waiting for the courts to process and decide on the claim: no matter the decision of the court, after their claims are processed, they are granted a fifteen day “grace period,” so to speak, in which they can leave the country without fear of deportation or detention (in theory to return to their country of origin, though many planned on using this time to reach the United States). And if their claims are successful, they might be awarded temporary visas that allow them to stay in the country for two to three months. Thus the invocation of legal discourses can give migrants the hope, or perhaps the illusion, of their identity as the bearers of rights, and, in some cases, migrants can mobilize the law to mitigate the precarity of their illegalized positions.

However, as the migrants we spoke to recounted their attempts to navigate Mexico’s legal system, they also expressed an awareness of the failures of the laws intended, in theory, to support them. Most obviously, some laws and policy reforms, such as Campaña “Corazón Azul,” have ultimately legally inscribed the state’s manipulation, exploitation, and mistreatment of migrants, as discussed in the previous subsection. Even when such practices are not occurring, though, the realities of the legal system can be punishing to migrants. As many expressed, the various levels of bureaucracy, paperwork and overlapping court systems can be almost prohibitively difficult to use, particularly for people whose status in Mexico is tenuous and who are uncomfortable making themselves too visible. Further, both the grace period and the temporary visas are ultimately stopgap measures, and finding ways through the law to gain more permanent legal status in Mexico or to escape the violence and prejudice of immigration officers and law enforcement agencies remain out of reach to most migrants. Perhaps the most daunting challenge in using the legal system to secure status in Mexico, though, is the spatialization of the written law, in that the legal code demands that migrants return to the place of their assault to file their claims, which often means heading back south and passing numerous checkpoints and perilous roads on the way. Thus the combination of the law’s bureaucracy and its particular spatial confines and demands imposes limits on its ability to make migrants the subject of rights, exacerbating the necessity of counter-machines that both navigate and work outside of the rule of law.

More punishing to the lives and attempts to be bearers of rights of migrants in Mexico, though, is the pervasiveness of the law without letter. The spectral practices that make up what we call the law without letter, related to and thought of as formal laws, but without actually being formally inscribed as such, include violence and deportations made in the name of Plan Frontera Sur, a program that exists in rhetoric but not in formal law or policy, the practice of holding migrants in jail indefinitely without charging them with any crime, and racially profiling people who supposedly look or otherwise seem like they are not from Mexico. These programs and practices, which have the specious appearance of the law, in being letterless and not subject to any formal code, treaty or standard of enforcement, become pervasive and spatially encompassing, making any migrant journey through Mexico a constantly perilous one in the context not only of actual legal discriminations, but also of ones invoked implicitly and discursively by systems of power. Further, in not being bound to any written law, methods like racial profiling or detention without charges can be and are used arbitrarily and unpredictably by a complicated network of police, military and legal networks. To use a Foucaultian formulation, the power of the law without letter is everywhere: not because it encompasses everyone, but because it emerges everywhere. In the face of this letterless, agentless, diffuse mode of law and policy, migrants and the actors and counter-machines who support them are left both vulnerable and unable to claim their subject position as victims of specific rights violations or unjust legal practices.

Thus the legal system and the practices that make up letterless law, though often invoked as protective forces for migrants, ultimately, or at least more often than not, exacerbate the fundamental precarity of the lives of migrants in Mexico. We might even say that under the auspices of the law without letter in particular, migrants undergo a form of civil death, in which they are produced as arbitrarily and uncertainly rightless subjects with no recourse to concrete law even as their bodies are managed and processed by structures of the legal system. While ostensibly migrants have recourse to the rights that various governmental agencies throughout their journey assure them are available, in reality these rights are difficult to come by and are undermined and undone by competing, encompassing legal fictions like chargeless detention.

In the wake of this nebulous, oppressive legal landscape, nongovernmental counter-machines become crucial to the existence and health of migrants in Mexico. Whether their focus is on providing migrants with care and comfort, like Albergue Jesús El Buen Pastor, or on encouraging migrants to resist power structures and unjust laws, like La 72 Hogar, one service that many counter-machines can provide, in lieu of or in addition to their efforts in relation to traditional human rights, is revaluing protecting the lives of people discounted and made constantly vulnerable by both the facts and fictions of the category of the law.

Spectrums of Politicization

Central to understanding the networks of machines, counter-machines, and actors involved in the struggle for migrant rights in Mexico is an understanding of the modes of politicization in which they operate and their ultimate goals along this axis. The NGOs and political groups devoted to the advancement of migrants that we saw all fall on a spectrum of politicization: some shelters seek primarily to care for migrants and offer them both physical and emotional services, while many other groups actively petition or act in rebellion against the government, legislature, and other official actors, politicizing the existence and violences of migration in Mexico as a larger issue.

Of the shelters we visited, Albergue Jesús el Buen Pastor is perhaps the least traditionally political, focusing most heavily on the bodily vulnerability and common humanity of migrants. Director Olga Sánchez Martínez, who has been recognized internationally and by the state of Mexico for her work, focuses on providing health care and work for the many migrants mutilated during their journey across Mexico. Identification with migrant suffering and with the individual value and humanity of migrants and the belief that every migrant has a right to life are both what prompted her to open her shelter and what continue to motivate her work. While Olga is not a political organizer, the international recognition she has received has allowed her to make an intervention in the hegemonic discourse of migration, in which migrants, and especially those living with disability after being seriously injured, are largely invisible and overlooked. Online accounts of Olga’s work, accompanied with pathos-inducing photographs of migrants with bandages and prostheses, appeal to an international audience to give care to migrants in the name of compassion and universal humanity.

But there are limitations to the empowerment of compassion and to the focus of Olga and others like her on individual migrants and their suffering. Olga does not seek to address structural causes of migration or demand that the Mexican or US government to take responsibility for migrants, making it so that the state and international organizations can commend Olga’s work as a saintly mother figure without having to take any action themselves. The image of migrant amputees demands compassionate care, but also reconstitutes the migrant as vulnerable and singular, accepting the larger conditions under which migrants migrate and are mutilated.

Other NGOs put more emphasis on the political identity and organization of migrants. One such NGO is La 72, a shelter founded in commemoration of the 2010 San Fernando massacre of 72 migrants with intensely ideological aims in relation to migrant rights. Recognizing that the statelessness of migrants and the arbitrary violence and biopolitical policing of Plan Frontera Sur make it impossible for migrants to assert their rights without fear of retribution, its founder Fray Tomás works towards the creation of new economic and social identities that will politically empower migrants individually and as a collective. In publicizing his demands, Fray Tomás often turning to traditional political strategies such as hunger strikes and protests, which Reguillo describes as the work of “residual” counter-machines. La 72 transforms migrant suffering into a shared history and narrative through Fray Tomás’ ideology, but also in the physicality of the space: the mural map of migrant routes through Mexico on one of the walls enables the sharing of survival knowledge, while the mural of key events in the history of Mexican migration and the 72 crosses memorializing the San Fernando massacre provide migrants with a sense of connection to each other and to those who came before them.

Fray Tomás’ dream of a radical, mobilized migrant collective is admirable, but his goal seems difficult. Drawing on a long history of Mexican labor activism, Fray Tomás argues that migrants can leverage their value as laborers in order to demand rights, but such a strategy does not account for the non-labor value that state and other exploitative actors increasingly extract from migrants through things like private detention centers that require migrants to pay for overpriced food or investment profits made from forcibly displacing people. Further, many migrants facing extreme economic hardship or violence are simply not in the position to collectively withhold their labor or publicly protest for their rights, while others might not want to. Cobbling together a functional collective from a population that is culturally and racially diverse and always in flux is challenging in and of itself, and the legally tenuous position of migrants in particular renders them at least partially dependent on Fray Tomás. They may independently try to assert their rights in future encounters with authority after they leave his shelter, as he hopes, but lacking a fixed collective political position and exploited not just by political structures, but also those of global neoliberalism, the migrants remain in a precarious state.

Between these two poles of politicization are shelters like Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes. Motivated by a political objective evident in its name, Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes seeks to provide migrants with assistance in navigating their journey through Mexico and knowledge about their rights and capacity as actors, but does not employ the same radical anti-state discourse that Fray Tomás does—indeed, while we were there, a worker from the federal Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos visited to inform migrants of their legal rights and to help them file claims. Even more structured around and perhaps capable of this work, though, are non-shelter NGOs like the Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías, whose more diffuse programs and leadership and lack of responsibility for housing services allow for potentially greater political action and for the building of collectivities. The Center’s goals are both concrete and ideological: put an end to detention centers, meet the health needs of migrants, advocate for the freedom of movement, and attend to the root causes of migration; its corresponding programs include monitoring detention centers and shelters, lobbying for policy changes, training migrants for job skills, learning about the problems in migrants’ countries of origin, and building networks through which migrants can share survival and assimilation strategies. Volunteers even plan to start a theater program based on Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed, which would allow migrants to tell their stories collectively.

Because the Center works with many migrants who choose to stay in Tapachula, the networks and collectivities it develops might be more likely to strengthen and last than relationships formed between migrants passing through shelters on their way to different destinations. However, in focusing on pragmatic policy aims, its capacity to provide the amount of personal care of Olga or to eschew the confines of the state like Fray Tomás are potentially limited. Further, in taking on and trying to work with, not solely against, government systems, the Center faces the inevitable difficulties of navigating the bureaucratic, sometimes-corrupt and profit-making state apparatuses and of using the master’s tools to dismantle his house, in Audre Lorde’s famous formulation. As Diego Lorente, the director of the Center puts it, he and his colleagues must complicatedly oscillate between being respectful and working with the state and being vocally critical of it.

NGO strategies for serving migrant populations clearly vary tremendously along this spectrum of politicization and, perhaps inevitably, any positioning has its particular drawbacks and limitations. Together these networks of shelters and centers, in their differing ways, do the important work of advocating for the human value and rights of migrants, both to state and international actors and to the migrants themselves, and some seek to accompany this revaluation of the migrant position with structural political changes. However, in order for a movement of migrants to be truly successful, the next step might be a politicization or collectivization of migrants not imposed by organizations, but more emergent from migrants themselves. The project now is to build towards a collective migrant identity and political formation based on networks of migrants, both stationary and in transit. In achieving this goal, we might think of Reguillo’s “emergent counter-machines,” which involve resistant performances, aesthetic expressions, and communities often formed and viralized through social media. These forms of resistance could serve as strategies alternate, migrant-based, capable of being dispersed, and variously political accompanying the work of official NGOs.

Interview with Diego Lorente, director of Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías de Córdóva, Tapachula.

We attend persons who have suffered institutional violence because they were not receiving appropriate treatment from the State. Then, we need to confront COMAR concerning asylum issues, or fiscalías that don’t do their investigation work, or even the Instituto Nacional de Migración for its labor of migrants’ detention and deportation. It is both a respectful and a confrontational relationship. We are the rock in their shoes; that’s why they don’t appreciate it.

Caring for Migrant Subjectivities

As earlier parts of this section and others have made clear, Plan Frontera Sur functions in large part through diffusely, pervasively managing the bodies of migrants in Mexico, allowing their death and making tenuous their existence in the country. In this sense, the letterless law of the Plan produces those who migrate not only as precarious, vulnerable subjects, but also as subjects that are given to unimportance and disposability in the eyes of actors in the governing machinery of Mexico, except perhaps in their function as possible sources of profit and exploitation from state and non-state actors. Through the increase in deportations and detentions, the impunity with which both governmental officials and civilians act on migrants, and the arbitrariness of deportation and detention practices, migrants are produced in the era of Plan Frontera Sur as bodies that do not matter, to use Butler’s formulation.

In this affective context of unimportance and marginalization, care becomes a powerful, resistant response that motivates the work of many actors and counter-machines seeking to improve the conditions of migrants in Mexico. This care, as we saw in our visits to shelters, can take many forms. Perhaps most explicitly focused on the reparative power and importance of care for migrants is Doña Olga, who has devoted years to providing migrants a space to stay for as long as they need to, giving them the opportunity to do arts and other recreational activities, and offering ongoing medical assistance, even providing prosthetic limbs, to those who are injured or whose bodies are mutilated in their attempts to cross Mexico. The actors at Albergue Jesús el Buen Pastor care for migrants both by continually providing them with necessary medical attention and by attaching importance and worth to them as people. Other shelters also seem infused with the affect of care, particularly in this latter mode, providing vibrant murals for migrants like those at La 72, or, more profoundly, offering them the agency to dance, have parties, like a celebration with a piñata happening as we arrived at La 72, be creative, use Facebook, or work in ways that they want to. These qualities of life at the shelters, though perhaps seemingly small, constitute a process of revaluing the migrants who stay in or pass through them, treating them not just as bodies to be managed or physically protected, but as subjects with personalities and emotions who deserve to be cared for affectively and whose desires deserve to be respected. Fray Tomás’ general focus on politicizing migrants who pass through La 72 and making them aware of their rights and value as subjects might also be considered a form of care in this framework, though one markedly different from and less driven by a discourse of compassion or medical services than Olga’s approach.

In these ways, some of the shelters and the actors in them orient their response to the biopolitical violence of Plan Frontera Sur and the machinery of the Mexican state around what Adam Rosenblatt refers to as the “process-focused,” reparative labor of care. Drawing on the Spanish term cuidado, or the “care-work” of practices like feeding, bathing, and clothing others who need help with these tasks, Rosenblatt explains that care, while it can be affective, also takes the form of durational labor “closely connected to repetition and ritual” and to the ongoing, maintained process of caring, rather than the production of outcomes. Though he focuses particularly on forensic work, we argue that this process-based care is also manifest in the work of shelters that receive a continual influx of migrants who are typically produced as disposable or simply as sources of revenue.

In this context, caring for migrants becomes not an act of charity or merely an affective response, but a powerful, political action: in caring for migrants, the shelters continually produce them as subjects who matter both in the space of the shelter and hopefully after they leave it, who are worth listening to and treating with respect, and whose personal histories, feelings and aesthetic or affective responses to things should be taken seriously. The work of care is radical, necessary, and audacious in the era of neoliberalism and Plan Frontera Sur, both in tending to the physical needs of migrants, but, more pressingly, in producing them as differently formed subjects, still precarious but not dismissable or external to the lives and lifestyles of Mexican citizens. Going further along this line, and thinking with Butler, the work of caring for migrants may even open up the idea that all of us, both those who give care and those who receive it, are dependent on and entangled with each other as humans, “given over from the start to the world of others,” inextricable from and dependent on them. Though Mexican state machinery makes migrants especially vulnerable, recognizing through care both their precarious position and their subjectivities might open the door to a more relational ethics or worldview, in which marginalized peoples are seen as agents and our more fundamental precarity, particularly at a time when states are increasingly declining to provide fundamental services for their citizens, is brought to the fore.

As easy as it is to be optimistic about care practices, though, hanging over care-based shelters and our discussion up to this point is the notion of care as patronizing, paternalistic, or a form of what Michael Barnett refers to as “imperial humanitarianism.” In other words, both the practice and the basic grammar of care involves caring for something or someone, a process which in spite of the actors’ best intentions can be centered on what the carer thinks is best for the person whom he or she is caring for. Fray Tomás, for example, though he undoubtedly takes seriously the needs and desires of those who stay at La 72, also prioritizes both in rhetoric and in practice his own hope that migrants will become politicized, radical questioners of authority. Other heads of shelters similarly have their own visions, often politically or religiously motivated, of what migrants need and how they can best care for them (the organizational structure of many of these shelters, as discussed later, might contribute to this trend).

Though the care that many migrants receive is undoubtedly beneficial, perhaps we should also take seriously the notion that some migrants see the shelters as a pragmatic way to continue their journey north, and might prioritize their more primordial needs over a larger project of reforming their agency, status in relation to Mexican political machinery, or capacity as political actors. As Fray Tomás noted during our interview with him, while some people who stay with him stay for weeks or months, some just want to pass through on their way north, aware of the dangers he wants to inform them of but not as focused on reconstituting their political position in relation to them or participating in the care revaluation practices like parties and artwork. The line between aid and paternalism and the different values of care as a provision of life-sustaining services and care as a fundamental revaluation of life thus become unstable and complicatedly charged in shelters that seek to help subjects both devalued and migratory. Migrant shelters that seek to care for migrants, particularly those like La 72 or Albergue Jesús el Buen Pastor, which, unlike others, do not have limits on the amount of time people can stay, must then, as Rosenblatt explains, begin and vigilantly continue the process of “observing, listening, rethinking, and revising” the forms of care they seek to provide.

Interview with Irineo Mujica Alzarte, director of Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria in Chahuites, Oaxaca.

Theological Counter-Machines: between Indifference and Activism

In recent years, Mexico has seen an influx of migration, particularly as Central Americans flee both state violence and organized crime in their countries and head through Mexico towards the “promised land” of the United States. While migration, as Gioacchino Campese points out, isn’t “a modern or postmodern phenomenon but an essentially human act,” the concept of undocumented migration, which happens “when a person enters, or lives in, a country where he/she is not a citizen, violating its laws and migration regulations,” has become an increasingly politicized and criminalized issue, frowned upon by governments and in the eyes of the public.

In a religious context, the contemporary phenomenon of migration, prompted in many cases by attempts to escape persecution, poses challenges for the construction of new theological perspectives on human mobility. Undocumented migrants are a group not just socially vulnerable, but legally deprived of rights due to their intertwined “statelessness” and “rightlessness” as Hannah Arendt puts it. In the face of this formalized rightlessness, though, officials in the Catholic Church maintain a discourse that presents the violences that migrants face as “misfortunes,” implying that what happens is tragic but unavoidable and overlooking the reality that the condition of migrants in Mexico is due to policy, legal injustice, and the concrete actions and decisions of state and paragovernmental actors. The widespread nature of this insidious discourse is due in part to the patriarchal, top-down structure of the Catholic Church, which creates the conditions in which people in positions of power set the tone and talking points on issues like migration, negating other voices from within the Church.

Indeed, migration in particular makes evident the divided position of the Catholic Church in Mexico—on the one hand, there is the hierarchy’s omission, indifference, and misrepresentation of the actual issues of migration, while on the other hand, much of the support for and interventions on behalf of migrants come from members of the Church. Although the division is, of course, not as binaristic as this, Mexican clergy members emerge who clearly belong to one camp or the other. Members of Catholic leadership, such as the retired and very influential Bishop Onésimo Cepeda, who was in charge of the Ecatepec Dioceses and who has remained close with controversial, powerful politicians, Veracruz Bishop Luis Felipe Gallardo and Xalapa Archbishop Hipólito Reyes Larios, from one of the most violent regions in Mexico, have demonstrated how Catholic theology and motivations can serve to benefit the government more than migrants and can collude in the oppressive, violent power and biopolitics that dominate large parts of Mexico. However, popular religious leaders such as Priest Alejandro Solalinde, founder of Hermanos en el Camino in Ixtepec, Oaxaca, Dominican Bishop Raúl Vera López, Saltillo, and Fray Tomás, among others, stand out for their intense, political, often religiously motivated labor on behalf of migrants.

Most of the shelters and migrant homes in Mexico are connected to parishes and managed by priests from this latter group or members of the laity somehow involved in religious activities. However, this structure does not necessarily imply institutional or financial support from the Catholic Church, and often the more distanced a shelter is from the Catholic Church the fewer resources it has at its disposal. For example, Carlos Bartolo Solís, a devout Catholic who abandoned his training to be a priest and who has been the manager of Casa del Migrante Hogar de la Misericordia in Arriaga for the last three years, explains that while the Catholic Church in Arriaga established his shelter and officially supports his mission, it has not offered financial support and has not been directly involved in his work. He told us that his day-to-day operations are primarily based on practical help from volunteers and some of the migrants, who maintain and clean the shelter and cook for the others. Some of this help has come from various independent actors motivated by their Catholic faith to engage in the emotionally and physically draining work of volunteering at a shelter: “we had Jesuit volunteers until May. Although we have looked for new volunteers, no one else has wanted to come.” The situation of secular Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria in Chahuites, led by Irineo Mujica Alzarte, is not far different. According to Mujica, the shelter is poor because it is not associated with any church, and it relies on nearby shelters, migrants, and members of the community to donate food and on unpaid volunteers to offer their time and labor. The absence of any official commitment of the Mexican Church towards the shelters and towards Catholic human right defenders like Solís also enhances their vulnerability to the many threats that they face from both Mexican governmental actors and organized crime groups.

The roots of the political division within the Catholic Church, which is also present in other countries in Latin America, between the institutional hierarchy of the Catholic Church and dissident members who work on behalf of migrants and other marginalized groups, may stem from the commitment of Catholics like Solís and Fray Tomás to liberation theology, the Latin American response to the Vatican Council II’s attempts in the 1960s to renovate Church theology and discourses. In 1971, Peruvian Dominican priest and theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez published Teología de la liberación: perspectivas, in which he articulated a theologically rooted approach to the oppressive, unjust social and political conditions affecting the majority of the Latin American population and founded the theory and practice of liberation theology. The Brazilian theologian Leonardo Boff, another important defender of a clerical commitment to a liberating praxis, followed, saying openly that European models of Catholic Church theology and organization did not acknowledge the voices of indigenous peoples and peoples of African descent in the Americas, who were and remain the victims of continued injustices. According to Boff, a new Catholicism in Latin America needed to be created, one based in the needs of marginalized peoples and one that imagined a Catholicism existing not just in the church, but in the world. It took fifty years for the Vatican to formally recognize liberation theology, which was a very uncomfortable religious proposal for many people in elevated positions in the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

In today’s context, another approach, based on the ideology of liberation theology, seems to be emerging in response to the current Latin American political situation: what we call a Theology of Migration. This Theology of Migration responds with a refreshed, liberating praxis rooted in the Bible to the vulnerability, political and social invisibility, and lack of rights of displaced persons and the structures of injustice acting on them. Tales of persecution-based migration and dispossession populate the Christian Bible, appearing in the Book of Exodus and others and informing the theological and historical foundations of the Christian faith, suggesting that a Theology of Migration might already have textual roots for practicing Catholics.

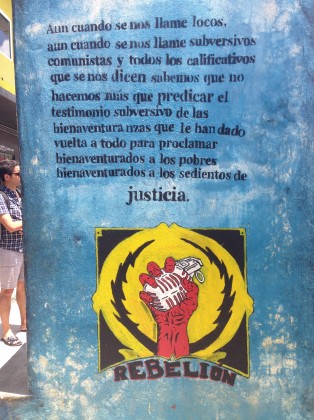

We might consider Fray Tomás an embodiment of this Theology of Migration. “Mexico is—to the shame of good Mexicans— one of most violent, unequal, corrupt countries, in which impunity reigns. Economic, political, and religious power in this country have united. The perros mudos [the silent ones, who do not denounce], the Church hierarchy, have joined those powers to hurt Mexican people,” he argues. Informed by liberation theology and very close to Zapatista movement, Fray Tomás is a charismatic, combative and, ultimately, religious leader who has dedicated his life specifically to helping migrants in Mexico, and he may be seen as the face of an emergent Theology of Migration. However, like the liberation theology that informs it, this newly articulated Theology of Migration and those who act motivated by it may be as uncomfortable or more so for figures in the Catholic hierarchy who take personal, political, and financial advantage of a rigid, exclusionary, and unbalanced structure of religious control. Again here Fray Tomás, who has been shunned, renounced, or ignored by various members of the Church and who often speaks of his break with the hierarchy, might be an example. “From the outset we have talked about autonomy, revolution and migrants’ new political and economic identity independently from the Church,” he affirms. “The Church used us and told us we should not speak beyond certain limits. But we haven’t listened. We are beyond and above the official Church’s morality. Here we defend life. This is our morality.”

The Mexican Catholic Church oscillates between a convenient indifference and an anti-institutional activism and emergent Theology of Migration that does not seek to change the establishment, but rather to work outside of it, creating micro-utopian spaces for migrants and caring for them both physically and morally. As Fray Tomás puts it, “the Church is for those who work it,” and he and those like him have worked it as a counter-machine in the context of larger violence and biopolitical control exercised by those in power in the Mexican government and, sometimes, in the Catholic Church. The Church that establishes shelters is not the same one that pretends to be blind towards migrants’ bare life. That committed Church, mostly led by those in lower clerical positions, is the space where a proper Theology of Migration, concerning displaced persons rights, can be raised—a crucial intervention in Mexico and Latin America, but also globally, where the violences of migrating in an era of biopolitics and neoliberalism loom large.

Interview with Carlos Bartolo Solís, director of Casa del Migrante Hogar de la Misericordia, in Arriaga

We can’t be indifferent towards the situation or reality the migrant is experiencing. The option is to denounce or be quiet. And there are times when it is necessary to shut up by precaution because we never know which kind of people we are dealing with.

Caudillismo as an Organizing Logic of Responses to Migration

Narrating capital-h History, as a narrative of the past’s most influential men and most dramatic moments, is a common practice in the composition of foundational archives in most Latin American nations. Since the 19th century, the revolutionary caudillo in particular has served as the embodiment of social movements and political projects, both in the eyes of history and of contemporaries. Coming from the Latin capitellus, meaning small head, caudillisimo refers to leadership of a cause or movement based on one strong, charismatic, central figure, who may even be thought of as messianic. It is characterized by a vertical and unidirectional interaction between the leader and “the masses” and involves a process of monumentalizing history and reducing sociocultural processes to a catalog of biographies, distilling the complexities of heterogenous collectivities to the biographical narrative of a single individual (who is usually male and masculinized). The familiar body and figure of the caudillo has often appeared as the most attractive, unitary symbol to represent and concentrate the process of history in countries like Mexico, and this trend has developed into a paradigm, establishing a way of reading the past and reproducing it in current social organizations.

In this subsection, we are interested in documenting and questioning caudillismo as a structural logic of the NGOs and shelters that we visited that seek to aid or house migrants. Our approach, rather than putting forth conclusive answers, allows us to explore different types of leadership and a broad array of characteristics of the shelters, revealing how the role of the leader of various shelters and NGOs informs the humanitarian and political projects of these organizations.

In Mexico, caudillismo echoed throughout the 20th century and has continued into the 21st, informing both readings of the past and understandings of the present. Since the 1920s, the representation of a complex, heterogeneous “guerra de facciones,” or war of factions, that extended across the national territory was organized under the umbrella of a few leaders, such as Venustiano Carranza, Francisco Villa, Emiliano Zapata, Ignacio Madero. This representational trend has continued to serve as a platform to imagine the concept of a unified, sometimes-mythologized revolutionary family and to efface the many fractures and disagreements that have actually characterized national history. Enrique Krauze’s 1976 Caudillos Culturales en la revolucion mexicana, in which he names high-profile national intellectuals, such as José Vasconcelos, Antoni Castro Leal, Alfonso Caso, as the other face of the revolutionary caudillo expands our understanding of this trend and of what might constitute caudillismo, adding intellectuals to the traditional military and political caudillos. Cultural programs, often promoted by the state, have in turn created an influential display of audiovisual and print production following the simplified logic of caudillismo; in this symbolic production of history, official narratives have obfuscated a more diverse historical process.

In the context of the contemporary, biopolitical violence in Mexico, specifically with regards to the status and vulnerability of migrants, we see the rise of a new type of caudillx that we wish to put forward here: the humanitarian caudillx, who takes over the representation of the Other in the public sphere, assumes the task of defending the voiceless migrants’ human rights, and confronts, in various ways, the governmental technologies that administer life and death. The humanitarian cuadillx also embodies a moral power distilled into his or her individual body that is, on occasion, able to shift the political agenda. In a Bourdieuian formulation, the humanitarian caudillx who has the power to speak and to speak for others is able to negotiate and wield his or her symbolic capital to challenge the state.

Perhaps the most iconic case in modern Mexico of a humanitarian caudillx is Javier Sicilia of the Movimiento por la Paz con Justicia y Dignidad, a poet and social activist whose son was murdered in 2011 and who publicly embodies the painful experience of disappearance in Mexico. Another actor who has been appealing to national and international media is the priest José Alejandro Solalinde Guerra, head of the shelter Albergue Hermanos en el Camino in Tuxtepec, Oaxaca. He might be one the most globally visible humanitarian caudillx, using his moral and religious capital to express his opinion sociopolitical matters, protect shelters, and denounce the Mexican state. Considering how Sicilia and Father Solalinde have been able to gain international recognition and begin to effect change is crucial in understanding how humanitarian caudillx in general develop their public voice to represent other, marginalized individuals and manage their image and the social and political capital that they build. In establishing themselves as moral, symbolic figures, developing individual relationships with other social and political actors, including those in government positions, receiving recognition from national and international institutions, and, increasingly, employing strategic social media personae, Sicilia, Solalinde and others are able to publicize the political issues that they care about, in large part through cultivating their personal relationships and their status as charismatic, magnetizing leader figures.

In our trip through southern Mexico, the leading humanitarian caudillx figures we came into contact with were Carlos Bartolo of Casa del Migrante Hogar de la Misericordia, Irineo Mujica Arzate of Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes, Olga Sánchez, who was recognized in 2004 by Mexican government with the National Prize of Human Rights and in 2009 by the Dalai Lama, Fray Tomás González Castillo of La 72 and Rubén Figueroa of Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano. These different actors embody the complexities and varieties both of forms of humanitarian caudillismo and of the goals of various caudillx. Olga, for example, visualizes her shelter as a place where wounded migrants can receive medical assistance and as a place for religiously-motivated compassion and charity. At the other end of the spectrum, we find Irineo Mujica, who organizes direct political actions with the collaboration of migrants to call attention to the role of the government and society in the violences of migration in Mexico. All of these people and the humanitarian work that they are able to accomplish, though, function at least in part through their public visibility and mobilizing charisma, a fact evident, for example, in the large role that Olga’s personal biography plays in publications for her shelter and in drawing volunteers and international attention to it.

Among these humanitarian caudillx, Fray Tomás is perhaps the one who most problematizes his own position. For him, the project of La 72 does not assume the representation of migrants under his name or the name of the shelter, but rather frames the migration process as a structural issue caused by governmental and private actors and seeks to advance a movement of civil disobedience and insurrection established by the migrants themselves. As he explains, La 72 aims to create new political identities for migrants that can accommodate different, individual ways of being, and compared to figures like Solalinda or Bishop Raul Vera, Fray Tomás himself keeps a relatively low public profile. Ultimately, Fray Tomás seems to want to displace the vertical logic of social mobilization, which threatens heterogeneity and which is subject to the traps and omissions of caudillismo logic generally.

Inevitably, though, in spite of his hopes and rhetoric, his movement and the changes he seeks to effect have been and will be organized around the figure and energies of Fray Tomás. Along with other leaders in the issue of migration in Mexico, he has the advantages of staying in place to establish relationships with local actors and to continue to work with new migrants and of a more high profile, less legally vulnerable subject position than the migrants he works with. Indeed, these challenges that Fray Tomás faces shed light on the general challenges of creating a heterogeneous, bottom-up movement for migrants in Mexico, a country in which the logic of caudillismo has a historically recognizable, powerful draw and in which migrants, in being illegalized, often cannot be publicly visible without serious repercussions. As the leaders we spoke with, and particularly those like Fray Tomás, Irineo Mujica Arzate and Rubén Figueroa, who overtly seek to create more inclusive, migrant-centered movements based on popular political action, continue their work, their stated aims and the realities of their effectiveness as caudillx figures will likely continue to exist in tension with each other, as they strive towards a form of humanitarian leadership without caudillismo.

Interview with Fray Tomás, director and founder of La 72 Hogar

Migrant Zapatismo

In her “Mobility and the Politics of Belonging: Indigenous Experiments in Creative Citizenship,” Mary Louise Pratt argues for el derecho de no migrar, or the right for indigenous peoples to claim “territorial belonging” and to not be forced into migration. To her and to the indigenous groups she discusses, native lands belong to the indigenous peoples who have historically lived on and through them. This claim by indigenous peoples to el derecho de no migrar might be thought of in coordination with Jesusa Rodríguez’s more culturally-centered notion of “deep Mexico,” or the aspects of Mexican culture that preceded colonization. Many people must work to preserve, value and reconstruct these cultural roots in the face of the project of an “imaginary Mexico” that wants to wipe them out in the name of “progress.” It is the struggle against the violences of imaginary Mexico and the insistence on el derecho de no migrar that partially inform the resistance of groups like the Zapatistas, who refuse to be geographically or culturally displaced, whether directly or as a result of neoliberal policy reforms.

Beyond Rodríguez’ imaginary Mexico and deep Mexico is a third Mexico, though, one that has emerged increasingly in recent years: Mexico as a vertical border, or a place to travel through for many Central American migrants bound for the United States. With the widespread state and organized crime violence in Central America and with the militarization of and increased scrutiny paid to migration policy since Plan Frontera Sur, this status of Mexico as a zone of migration, of permanent impermanence, and the precarity of life for those who experience it as such has become especially pronounced. The migrants who live borderized Mexico do not share the geographic and historical relation to Mexican land of the indigenous people arguing for el derecho de no migrar, and, in fact, in many ways they have an opposed relation to the spaces they travel through. However, they, too, are clearly subject to the same profit-making violence, human rights violations, and criminal apathy of the neoliberal Mexican state and paragovernmental entities, which form a “system that’s tried to make them disappear.”

Both Zapatistas and migrant rights activists like Fray Tomás acknowledge the shared marginalization by the forces of imaginary Mexico of indigenous communities, discriminated against for their “’natural (racial) inheritance” and migrants, discriminated against for their “’alien’ (juridical) status.” Further, there exist coalitional possibilities in the struggle for rights, or for separation from the Mexican government, for both the people who have been in Mexico for thousands of years and those who are passing through it: Zapatista communities have allowed migrants in their territories and have offered them food and medical attention, while Fray Tomás’ rhetoric and the murals by Zapatistas covering the walls of La 72 indicate the inspiration from and possible alliance with the Zapatistas motivating his mission.

However, putting these two movements in conversation with each other also sheds light on the specific difficulties of the more recently-urgent struggle for migrant rights in Mexico. Unlike many migrants, especially those first entering the country, the Zapatistas have an ingrained, even militant sense of the rights they are owed, have been owed historically, and insist on claiming and of their political power as an entrenched, organized community. By definition, migrants passing through Mexico, who are transitory and whose existence is illegalized for as long as they are in the country, do not have recourse to these strategies: they have neither historic claims of and assuredness about what they are owed, nor the opportunity to collectivize and resist durationally as the Zapatistas have. Thus people like Fray Tomás end up taking on the work of publicizing, continuing, and creating rhetoric around the struggle for the rights of a group that cannot be as collective nor as visible as the also-marginalized indigenous groups the Zapatistas fight for and belong to. While he and his allies advance in their struggle and have a profound impact on the lives of migrants, their capacity to form a larger migrant movement remains uncertain.

The question for migrants and those who seek to mobilize on their behalf then becomes how a class of marginalized peoples in Mexico whose roots are not deep, but rather transitory and borne of necessity, might mobilize and insist on el derecho de migrar under the pressures and violence of imaginary Mexico. How can a Zapatismo ideology and Mexico’s larger revolutionary history inform the struggle of people who do not necessarily belong to or work the land they pass through, nor seek to claim it, but who also face the violences of neoliberalism and bad government?

Though these questions remain and remain potentially unanswerable, we might begin to see in the work of Fray Tomás and those like him the possibility of a diffuse Zapatismo. While Fray Tomás may not be able to organize coordinated, entrenched and militant communities like the Zapatistas, his stated hope is that migrants leave La 72, which he thinks of as an autonomous zone like a Zapatista community, with a new sense of themselves as fighters, rights-bearers, and resisters of authority: he seeks to help them realize their power to resist and organize against the forces that would claim to have power over them. The migrants with these newly mobilized identity-formations, reminiscent of those of the Zapatistas and hearkening back to historical political and religious revolutionary discourses, do not remain in an organized, resistant community, though, but instead travel on with them. These radicalized senses of rights and identity may and probably do make a huge difference in the lives of individual migrants. But perhaps we may also begin to look for the larger, more collective effects, resonances, and afterlives of this work and of a Zapatismo identity that has been repurposed and that might migrate. With many migrants increasingly using social media to gain information about their journeys and stay in touch with people they meet and with groups like Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes actively fostering these social media engagements, the possibility of a Zapatismo or revolutionary ideology that is both diffuse and collectivized seems increasingly possible. As Benedict Anderson first illustrated, “imagined communities” like these ones formed online can and have sparked dissident nationalisms and new political formations. Such an outlet for imagined community building is perhaps the tool with which radical migrant Zapatismo can be collectivized and mobilized in new ways.

Coda: Empty Chairs

The chair is empty. Someone has just left, someone could not come, someone will not come. Chiapas is littered with empty chairs—vacant, vacated, unfilled, unavailable under the specter of migration. The chairs continue to be empty, despite so many promises and plans and programs and official speeches and policy reforms and invocations of God’s grace and intentions to defy the state and the best intentions and. And yet. The chair is still empty, will remain so.

The chair is empty because displaced people (migrants, refugees, victims of civil wars, of environmental destruction, of neoliberalism) are invisible, even as they are invoked in uncountable pages of uncountable documents produced by uncountable international agencies and national organizations. Migrants become data, become commodities, become stateless, become job-takers, welfare-thieves, criminals, illegal, depending on one’s point of view. They remain invisible. Why care about invisible, unwanted individuals? Once a migrant without the requisite, metonymic papers crosses a line, she loses the right to have rights, and her existence is produced anew in the machinery of the state. Bare life. Precarious life. Illegal life. Invisible life. Life that cannot be seen in the chairs of courtrooms, of government chambers, of human rights organizations.

The chair is empty because he or she or they—Guatemalan, Salvadorian, Honduran, Nicaraguan, Cuban—must leave after three or four days in the shelter. Yes, yes, these are the rules, I’m sorry: resources are limited. For some of the guests (guests?), it doesn’t matter: they want to take the next train anyways, whenever it comes. Others are waiting for Godot in the form of a humanitarian visa always promised but never arriving, or a positive answer for an asylum request, or any help to move forward, to make life not quite so untenable.

The chair is empty because on 8 August 2015, 14 Hondurans who had arrived at La 72 just the day before decided to take the train that was expected for that evening. After a tiring journey and so many hours walking, one good night of sleep, some meals, and some moments of repose were enough to refresh them. During that short period at the shelter, all of them became part of a communitas, ephemeral and microutopic, meeting beyond established social structures and the law. They filled new chairs. That experienced communitas dissolved once they stood from their chairs and passed through La 72’s door. The shelter is an intermediate station, but not the final destination. That chair needs to remain empty for the next one, and they have new chairs to aim for, to hope that they can fill.

The chair is empty because the state is a machine. Whom do you accuse when a dizzying array of local, state, national, military and private actors are policing the border and the country, a kaleidoscope of variegated uniforms? Whom do you turn to when the federal Comisión de los Derechos Humanos publishes policy unsigned, unnamed? Corporations are the state and they are people, but how can a corporation fill a chair? Who are the agents of Plan Frontera Sur? They might be under a mask, but the mask might also be covering nothing—facades all the way down, as the Zapatistas suspected. The chairs that should be occupied by a long list of actors—presidents, ministers of this, ministers of that, representatives from official commissions of human rights, archbishops, directors of national and international bureaus, military leaders—are not. The chair in which the person accused, the subject of the lawsuit, the person to denounce remains unfillable. This is perhaps the endgame of the meeting of biopolitics and neoliberalism.

This is the machinery of empty chairs for migrants. A machine that does not allow Karolinas, Wilfredos, Samuels, Manoels, Luises, Jorges, Pamelas, Jahaíras, Isabels, Evelins, and Emersons to take their places. A machine that tries to keep people like Ruben Figueroa, Carlos Bartolo, Irineo Mujica, Gerardo Espinosa, Diego Lorente, Luis García Villagrán, Fray Tomás González, and Alejandro Solalinde constantly far from the chairs they aim to fill. A machine that allows Enrique Peña Nieto, Otto Pérez Molina, El Chapo, Humberto Mayans Carnaval, Juan Orlando Hernández, Carlos Slim, and Ardelio Vargas Fosado to leave vacant the chairs they should sit in. A machine in the business of constantly producing and taking away chairs that are not allowed to be filled, that need not be filled, or that elude being filled.

Where are the 14 Hondurans who left their chairs at La 72? Are they still together? Are they still on their way? Are they all alive? Are there available chairs for all of them where they’re heading? To this last question, at least, we can hazard an answer. The network of faceless, protected decision makers who have control over life and death has answered this question for us, continuously promoting a game in which thousands of people round limited places to sit—the permanent last round of biopolitical musical chairs. Only a few of them will get the chance to go ahead. The others become statistics in some governmental report disseminated everywhere, written by no one, charging no one.

Ultimately, this is the machinery against which our counter-machines, actors, and networks act, struggling to produce more chairs and to fill those that seem to be always already empty. Perhaps they are simply rearranging deck chairs on a system that is the Titanic for migrants. But each chair produced and filled contains a promise beyond its limitations: “chair or no chair: a binary relation. But the vicissitudes of moving a body around are infinite. You never know what a person in a chair can do.” The Sisyphean project of filling chairs will and must go forward, as those who fill them or allow them to be filled can then sit in them aslant, subversively, anew. The great work, fraught with difficulties internally and externally imposed though it may be, continues.

Krauze, Enrique. Caudillos culturales en la revolución mexican. Mexico: Siglo XXI Editores, 1976. Campese, Gioacchino. 2008. Hacia una teología desde la realidad de las migraciones: método y desafíos. Jalisco: Catedra Eusebio Kino SJ, Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso, De Genova, Nicholas. 2013. "Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion." "Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion." Ethnic and Racial Studies 37. no. 7: 1180-1198. Miller, Todd. 2014. "Mexico: the US Border Patrol's Newest Hire." Al Jazeera America, 4 Oct 2014. http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2014/10/mexico-us-borderpatrolsecurityimmigrants.html. Barnett, Michael. 2011. Empire of Humanity: A History of Totalitarianism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, Grimson, Alejandro. 2003. "Los procesos de fronterización: flujos, redes e historicidad" Fronteras, Territorios y Metaforás. Edited by Clara Ines Garcia. 5-34. Medellin: Hombre Nuevo Editores, Kunz, Marco. 2008. "La frontera sur del sueño americano: La Mara de Rafael Ramirez Heredia" Negociando identidades, traspasando fronteras: Tendencias en la literatura y el cine mexicanos en torno al nuevo milenio. Edited by Susanne Igler, and Thomas Stauder. 71-82. Madrid: Iberoamericana Libros, Reguillo, Rossana. 2011. Translated by Margot Olavarria. "The Narco-Machine and the Work of Violence: Notes Toward Its Decodification." Emesferica 8. no. 2: Accessed 10 Aug 2015. Lorde, Audre. 1984. "The Master's Tool Will Never Dismantle the Master's House" Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. 110-114. Berkeley: Crossing Press, Castles, Stephen. 2010. "Migración irregular: causas, tipos y dimensiones regionales." "Migración irregular: causas, tipos y dimensiones regionales." Migración y desarrollo 7. no. 15: 49-80. Foucault, Michel. History of Sexuality: Volume 1: An Introduction.. trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage Books, 1978. Arendt, Hannah. 1973. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Orlando: Hartcourt Brace & Company, Boff, Leonardo. 1985. Church, Charism, and Power: Liberation Theology and the Institutional Church. New York: Crossroad, Bourdieu, Pierre. 1979. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. New York: Routledge, Pratt, Mary Louise. 2016. "Mobility and the Politics of Belonging: Indigenous Experiments in Creative Citizenship" Resistant Strategies. Edited by Marcos Steuernagel, and Diana Taylor. New York: HemiPress, http://scalar.usc.edu/works/resistant-strategies/mobility-and-the-politics-of-belonging-indigenous-experiments-in-creative-citizenship. Rodríguez, Jesusa. 2016. "500 Years of Resistance" Resistant Strategies. Edited by Marcos Steuernagel, and Diana Taylor. New York: HemiPress, http://scalar.usc.edu/works/resistant-strategies/500-years-of-resistance. Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso, Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing, Manguso, Sarah. 2008. The Two Kinds of Decay. New York: Picador, "Peña Nieto pone en marcha el Programa Frontera Sur." 2014. Animal Politico, 8 Jul 2014. http://www.animalpolitico.com/2014/07/en-esto-consiste-el-programa-que-protegera-a-migrantes-que-ingresan-a-mexico/. Shmidt Camacho, Alicia. 2006. "Integral Bodies: Cuerpos Íntegros: Impunity and the Pursuit of Justice in the Chihuahuan feminicidio." Emesférica 3. no. 1: Accessed 10 Aug 2015. Gutiérrez, Gustavo. 1971. Teología de la liberación: perspectivas. Lima: Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones, Rosenblatt, Adam. 2015. Digging for the Disappeared: Forensic Science after Atrocity. Stanford: Stanford University Press,