Section Menu

Introduction: the Performance of Control and Security

Walls and Borders

Revelations: Crossing the Suchiate River

Checkpoints

Listening to the Border

Introduction: the Performance of Control and Security

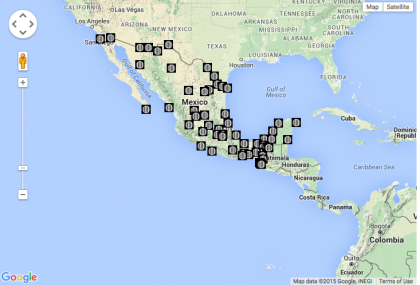

This section examines the performance of control and security in southern Mexico, which shares a 541-mile border with Guatemala. Aside from 11 official migratory stations, there are also at least 370 informal crossing sites. It is therefore very hard to “secure.” The visible presence of multiple checkpoints—or internal “borders”—exists in stark contrast to the porousness of the physical border between Mexico and Guatemala. The dissonance between the militarized performances of “border” security at the checkpoints and the daily movement of informal migration across the river that marks the Mexican-Guatemalan border makes evident that the goal of “border security” in southern Mexico is not to halt migration, but rather to intensify insecurity through the criminalization of migrants and the diffuse production of a surveilling gaze. The insecurity produced through the decentralization of “border security” has manifested a political and humanitarian crisis wherein Central American migrants fleeing physical violence and economic hardship in their home countries become the targets of violence and economic extortion all along the migrant route.

On 7 July 2014, Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto and President Otto Perez Molina of Guatemala inaugurated Plan Frontera Sur, a strategy to reinforce “security” in the southern part of the country while promising security in the form of human rights measures for migrants. The United States has provided millions dollars for equipment and training.

A recent Congressional Research Service report by Clare Seelke notes, “The State Department has provided $6.6 million of mobile Non-Intrusive Inspection Equipment (NIIE) and approximately $3.5 million in mobile kiosks, operated by Mexico’s National Migration Institute, that capture the biometric and biographic data of individuals living and transiting southern Mexico. The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has also provided training to troops patrolling the border, communications equipment, and support for the development of Mexico’s air mobility and surveillance capabilities.

Murals and posters everywhere assure migrants that they have rights. But Plan Frontera Sur has only augmented the violence against them.

Migrants now have to circumvent the checkpoints by walking off the road, into the bushes and woods. Criminal gang members and delinquents often wait there to kidnap, rape, and rob them. As Gerado Espinosa, Director of Research for the human rights organization Por la Defensa de la Vida y la Dignidad Fray Matías de Córdova in Tapachula, Chiapas, said, “the worst enemy of migrants is the program for the assistance of migrants.” While Plan Frontera Sur has reduced the numbers of people taking the train

[La Bestia]

80%, it has done nothing to diminish the number of migrants. The reason for this, both migrants and officials told us, is that migrants leave their home countries not because they want to, but because they must in order to survive: the violence and economic crisis at home makes it impossible to stay. So migration has not decreased, even though the number of checkpoints has more than doubled. The estimates are that 800-1,000 people cross Mexico’s southern border every day. But the route has become more dangerous, and the military, state, and federal agents charged with protecting migrant rights are regularly charged with violating them.

As Butler argues, the category of being considered “human” is contingent on the existence of an epistemological frame that allows people to be read as human.

The migrant, as a criminalized and stateless transient being is rendered a surplus and therefore disposable entity.

Through the legal production of their illegality and the performed spectacle of border security, the migrant is included as always excluded.

Rendering the migrant rightless and disposable, s/he becomes a source of profit for organized crime and petty criminals who kidnap or rob him/her, for families back home who live off of remises, for businesses that profit from cheap labor, and for nation states that receive funding to address the migrant crisis and bolster “security.” Within both the United States and Mexico, undocumented Central American migrants become a highly exploitable and invisible workforce. Detention centers and jails are money-makers. Siglo XXI, the largest detention center in Mexico, bears the same name as Century 21, the international broker for those who can afford to buy homes. In the twenty-first century, this ironic juxtaposition reveals, populations are housed either in jails or in upscale homes and gated communities—all in the name of “security.” Migration has become big business, lucrative for everyone except the migrant. The migrant, then, becomes a valuable commodity and, at the same time, utterly disposable.

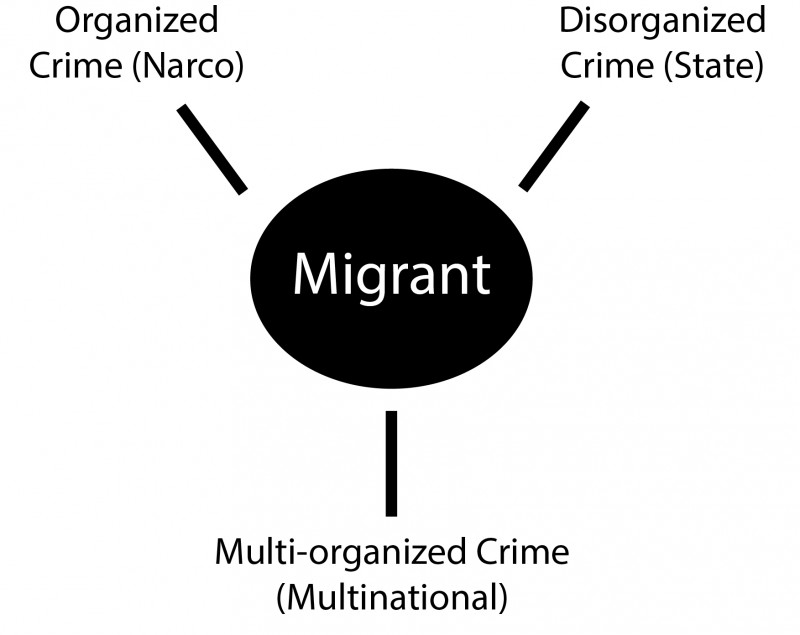

As formulated by Jesusa Rodríguez in one of our courses, migration’s profiteering actors are centered around the interaction of three major forces: the organized crime of narcos and other gangs; the disorganized crime of the Mexican state; and the multi-organized crime of multinational corporations. Whereas the undocumented migrant, made into a criminal, becomes the raw material at the center of the geopolitical “necropolitics” of southern Mexico’s border security, those who profit from the production of migrant insecurity exist on a spectrum of visibility—given to be seen—and invisibility—given not to be seen. Situated at the most visible end of the spectrum is organized crime, followed by the disorganized crime of the Mexican state, leaving the multinational corporations’ multi-organized crime to occupy the privileged position of being given not to be seen.

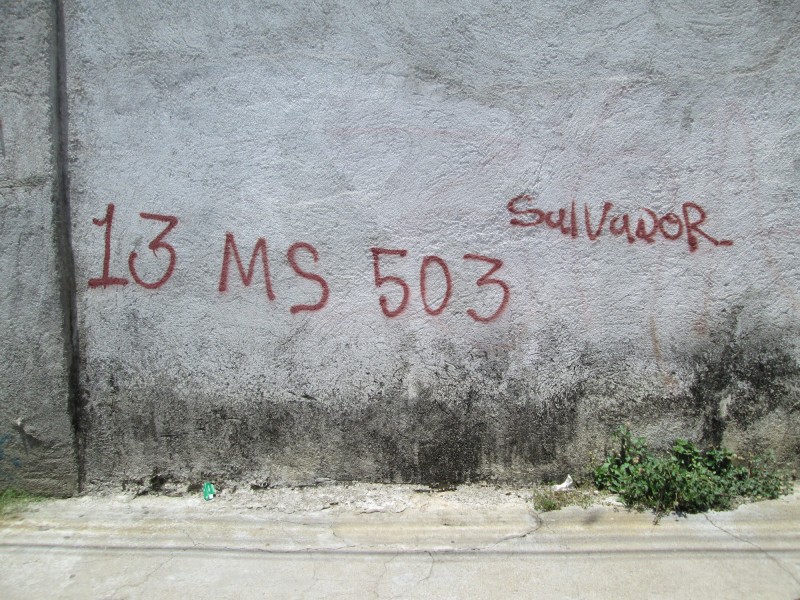

Through their opportunistic profiteering, organized gangs such as the notorious Maras and Zetas perform the role of the given to be seen: the dead and wounded migrant bodies are often the visible markers of their power. In turn, the gangs provide the justification for increased investments in security technologies. Part of the death world that Achille Mbembé writes of, the Maras and the Zetas occupy a place in which they are its products, its instrument, and its victims. The Maras, originally comprised of deported youth from the Los Angeles area, have turned into opportunistic killers. The Mexican state also kills, kidnaps, and robs migrants, but it masks its corruption and complicity in the violence against Central American migrants by blaming “human rights” violations on organized crime. Both organized crime and the disorganized crime of the Mexican state in turn function simultaneously as instruments of and a smokescreen for the multi-organized crime of multinational corporations and the international states that do their bidding.

The mechanisms of control, as seen in this section, include terror, fear, and silencing. The “terror system,” in Michael Taussig’s words, is diffuse: it passes “from mouth to mouth, from page to page, from image to body.”

It works through the showing of physical remains (the dead and tortured bodies of migrants) and the threatening of human rights defenders, journalists, and all who threaten its power. Checkpoints and passports, on the other hand, bolster the military’s performance of “order” and “control.” However both the terror and the control are two sides of the same coin—Siglo XXI and Century 21.

Walls and Borders

Recording of the River Suchiate

Mexico shares a 541-mile border with Guatemala. Aside from eleven official migratory stations, there are also at least 370 informal crossing sites. Migrants cross the Usumacinta River, the Salinas River, and the Suchiate River on rafts and boats. An estimated 800-1,000 people cross Mexico’s southern border every day. People have transversed this “border” for millennia. Mayan communities have lived in this part of the world since around 2600 BC. The political border is contemporary, dating to 1882.

What does this border, which looks so different from Mexico’s northern border with the United States, suggest about what Nicholas De Genova calls the “border spectacle” and the spectacle of “illegality?”

The southern border might be described as an “anti-spectacle.” Young boys and men push the rafts quietly back and forth across the river. People get on and off, paying their 20 Mexican pesos each (a little more than one dollar). No one stops them. No one asks questions. Everyone disperses.

Wendy Brown argues that walls perform a sense of sovereignty in a post-sovereign world. Walls literally cement the differentiation between insiders and outsiders. They promise to secure, protect, and secure the feeling of national identity.

The anxiety of the “waning state” is restored through the militarization and masculinization enabled by the modern border. Walls underwrite the performance of potency, might, surveillance, force, and intelligence. The construction of walls, then, is constitutive of modern subjectivities. Walls materialize illusions of impenetrability. Walls perform the

“desire for a national image of goodness” that “externalizes the nation’s ills” and disavows aggression. The US-Mexican border is “political theater.” The effects of this performance of control is the production of the border zone as an “increasingly violent space.”

Borders, Claudio Lomnitz posits, involve a “process of naturalization of politics [….] the political border functions with pedagogy, a national pedagogy.”

How does the imposing visibility of Mexico’s northern border wall contrast with the anti-spectacle of Mexico’s southern border? The southern border is characterized not by the performance of law and legality, but of lawlessness. The border economy flourishes with people buying and selling pesos, quetzales, clothes, services, drugs, sex, and other goods. Everyone, it seems, is involved in what is called the “bisne” (or business) fueled by migration. Unlike the northern border, the southern border is not spectaculized: it is normalized. It is absolutely penetrable. If walls contribute to a national sense of US impregnability and militarization, the southern border reflects a nation that, as Octavio Paz argues, has historically felt itself to be comprised of “sons of la Chingada” (literally, the fucked and penetrated mother). In the essay “Sons of La Malinche,”he writes:

The person who suffers this action is passive, inert and open, in contrast to the active, aggressive and closed person who inflicts it. The chingón is the macho, the male; he rips open the chingada, the female, who is pure passivity, defenseless against the exterior world. The relationship between them is violent, and it is determined by the cynical power of the first and the impotence of the second. The idea of violence rules darkly over all the meanings of the word, and the dialectic of the ‘closed’ and the ‘open’ thus fulfills itself with an almost ferocious precision.

Mexico’s northern and southern borders—respectively closed and open—enact the violence of contact zones and crossings that make up migration. The borders are two sides of the same coin, performing national imaginaries rather than, as Brown puts it, achieving their “putative aims.”

In neither case do the borders respond to the ways in which capitalism works. Even the seemingly insurmountable obstacles of the northern border are porous enough to let migrants in when capital needs them. Uncertainty and ambiguity, rather than control, keep migrants on their toes. No one passes today, but maybe tomorrow?

The law is a fluid fiction; rules are always shifting. Walls are always about something else.

Revelations: Crossing the Suchiate River

Hailed by our very own Trans Jesús-a, we arrive in Cuidad Hidalgo, at the Mexican-Guatemalan border, shortly after sunrise. After the dozens of checkpoints we’ve encountered on our journey thus far, the absence of security is an astounding “revelation.” A flotilla of rafts nonchalantly transports people and goods in both directions across the Suchiate River, which separates Mexico and Guatemala. For those who either don’t have the money or choose not to pay the 20-peso raft fee, the river is shallow enough in places to walk across. Emboldened by the ease of transport across the river, we decide to embark upon our own en masse migration.

Walking the streets of Ayutla, Guatemala on the other side, we are aware of ourselves as a spectacle. Why are we here? Clearly, we are a group of (mostly and relatively) privileged Gringos. So why didn’t we cross over the bridge—the official border crossing—several hundred yards down-river? Our stay is brief, a half-hour wander before we return to the rafts that ferry us back to Mexico, where our air-conditioned bus (another spectacle) awaits us. But first, perhaps tad anxiously, we wait for the arrival of members of our group who are lingering on the “other side.” As one of our group members explains:

Most of the group crossed back over the river. A few of us stayed behind to wait for our ‘missing’ photographers—Susan Meiselas, Moysés Zúñiga, Raymundo Marmolejo, and Gabriela Bortolamedi. Translating for the English-speaking members of our group, Pablo tells us what someone nearby has said: ‘Look at those Gringos pretending to be wet backs.’ We go for a walk and are stopped by a group. (I thought they looked sketchy, because of how they were watching us.) But they tell Pablo they were watching us because they didn’t want anything bad to happen to US tourists. So, indeed, they were watching us, like I thought, but it was to protect us, not to hurt us.

Checkpoints

One of the main objectives of Plan Frontera Sur is

“improvements in infrastructure, for border security and migration;” this goal was realized through the increase in and enhancement of different checkpoints, specifically in Chiapas. This “improvement” was visible on the road we traveled in an attempt to map out some of the routes taken by migrants crossing Mexico to El Norte, or the United States. In fact, in most of our checkpoint encounters, security and control were exaggerated and highly performed. For instance, within a few hours on the road to Palenque, we passed by five checkpoints (two federal, as well as ones run by immigration control, the marines, and the military), all of which had different levels of security measures. The most elaborate checkpoints seem to be the military ones, with soldiers holding weapons roaming the area, stopping cars, or standing behind their Lego-like barricades.

Other checkpoints have clearly structured buildings that contain multiple kinds of surveillance technologies, including, but not limited to, cameras and sensors.

In National Migration Institute checkpoints, the measures of checking security are performed in an organized and mundane manner. On the way from Tapachula to San Cristóbal, we were stopped twice for the purpose of checking our documents. In both cases, a woman dressed in a uniform entered the bus smiling. During the first stop, the official went around greeting people with a smile and a soft “hola,” while asking to see their passports. With a swift inspection, she handed them back with a nod and a “gracias.” At the next stop, the official simply entered the bus smiled, nodded, and then left. Out of the many checkpoints that we went through, we passed through most of them with little inconvenience. On the first leg of our weeklong trip, we were asked only once to stop, leave the vehicle, and show our documents. This, of course, is not the case for everyone passing by these security checkpoints. Aside from our stamped passports, which allowed us to be relaxed and smile back while our documents were being inspected, our own spectacle of privilege was on display as we roamed the streets and highways of Chiapas. The large, air conditioned bus, filled with students who seemed clearly foreign and touristic-looking, provided physical and symbolic immunity. In a way, this bus acted as our safe haven, our passage right, or as a spectacle rendering us “legal” in the eyes of the state.

Our “gringo” immunity was called into question when our group split during the end of the week, with some sticking to the schedule and traveling to the Mayan ruins at Palenque, while others stayed behind at La 72 Hogar migrant shelter. On the way back to Palenque from La 72, Tamara, a Canadian student, was caught without her travel documents at a migration checkpoint and detained. She witnessed control and security performed by multiple actors, who processed and documented her on suspicion of illegal immigration. Inside, she saw women and children behind bars and a chart on the wall indicating that there were 83

people inside and listing the detainees’ countries of origin and demographic information. There was an American citizen who was caught without a passport stamp who was suspiciously never listed on the population chart. Tamara was released after six-and-a-half hours of detainment, when someone from the other group arrived with her passport. This confirmation of her citizenship forced the immigration authorities to release her, as did the resistance, protests, and threats of legal action made by her classmates and volunteers from La 72. A brief interview with Tamara is below, in which she explains the experience of detainment in more detail.

While the performance of security on the roads in southern Mexico has been successfully manifested, this performance has a much darker side, as witnessed by Tamara and, more gravely, those migrating from Central America who are caught without documents. For despite Tamara’s detainment, our experience of these security measures was generally far removed from the experience of migrants attempting to get through Mexico. Central American migrants hoping to reach El Norte are systematically secluded and imperiled by being pushed into the mountains to avoid checkpoints. Thinking that they have passed the danger of borders once they cross into Mexico, migrants find themselves in a position where this border is diffused and fragmented into smaller physical borders within the country. This form of policy results in the constant reaffirmation of what the law considers their “illegality,” allowing implicated governments to perpetuate their criminalization. Under the guise of ensuring order and national security, migrants are subject to further exploitation.

At Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes, we met Carolina, a migrant from Nicaragua, who explained to us that a road that would take an hour using a bus or car takes her and other migrants four days of walking in the mountains. Having left her family in Nicaragua for economic reasons, Carolina is now going through a great deal of hardship trying to cross to El Notre without having enough information about the mountain routes. She describes these routes as extremely dangerous, especially for women. Migrants taking these hidden routes are under the constant threat of gang members and petty criminals, migration control and checkpoints, and the hard nature of a route devoid of water, resulting in countless assaults and injuries. With these threats haunting them, migrants do not seem to have any option other than to further disappear from the “official map” of the country, protected only by the dark of the night and the desolation of the steep mountains.

Listening to the Border

One of the most striking aspects of our trip through the southern border of Mexico was the duality of the visible and invisible performances of security in relation to Plan Frontera Sur. We saw (and in some cases experienced) countless border checkpoints, police and army officials, and caged migration vehicles used to transport detained migrants. Yet at the same time we saw nothing: empty train tracks, open fields, quiet streets. How do we translate this tension between visible and invisible to the audible realm? What are the sounds of the migration process? I have listed a small collection of recordings from myself and some colleagues who recorded the spaces of migration. What we can hear is much like what we see: apparent normality and everydayness, which leaves me feeling deeply unsettled—a terrible crisis is unfolding in Mesoamerica, yet often, as in other moments of historic violence, everyday life looks and sounds normal.

Train in Arriaga

These recordings were taken on 3 August 2015 in downtown Arriaga. Before the implementation of Plan Frontera Sur this space was the first stop for many of the migrants travelling north. Because of changing migration routes, the use of the train has become less popular, though we did encounter three young men. Most of what we saw (and heard) was starkly different than it likely would have been in previous years.

Tapachula Street Singers

This recording is of a young man and women singing Evangelical hymns from memory. Although the recording is brief, they were at the corner from most of the afternoon.

Talisman Border

As opposed to the raft crossing at the unsupervised Paso del Coyte at the Suchiate River, the Talisman Border was heavily supervised with migration officials, municipal police, and the national army. This heavy state presence aside, our brief time there was fairly tranquil. We could hear people selling coffee, children playing, and migrants crossing below the bridge on raft and foot. After passing through a steel turnstile, we were met by a Mexican immigration official; although we didn’t present our passports, our reentry into Mexico was unhindered.

Estación de Tren Chontapla

At the time of this recording, the locomotives (one of which was a US-made Union Pacific) were under repair. There were still several young men waiting along the tracks, though, for another train to come later that day.

The Suchiate River

The Suchiate River marks both the border between Guatemela and Mexico and the beginning of some of the most dangerous parts of the migration north. None of this is audible in this recording of a calm river in the early morning.

Arriaga Cemetery

Much like the Suchiate River, the Arriaga Cemetery was a quiet space that that implicitly marks the danger of migration north. This recording allows us to listen to the serenity of a space that hosts paupers’ graves for those migrants who have perished in and around the Arriaga leg of the crossing.

Mbembé, Achille. 2003. "Necropolitics." "Necropolitics." Public Culture 15. no. 1: 11-40. Paz, Octavio. 2008. El laberinto de la soledad. Edited by Enrico Mario Santí. Madrid: Cátedra, Lomnitz, Claudio. 2016. "The Origins of Our Supposed Homogeneity" Resistant Strategies. Edited by Marcos Steuernagel, and Diana Taylor. New York: HemiPress, http://scalar.usc.edu/works/resistant-strategies/lomnitz-the-origins-of-our-supposed-homogeneity-eng. Brown, Wendy. 2010. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty. New York: Zone Books, De Genova, Nicholas. 2013. "Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion." "Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion." Ethnic and Racial Studies 37. no. 7: 1180-1198. Matías, Pedro. 2015. "Por extorsión y secuestro denuncian a funcionarios del INM." Proceso, 11 Aug 2015. http://www.proceso.com.mx/?p=412743. Taussig, Michael T.. 1992. The Nervous System. New York: Routledge, Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso,