Section Menu

Introduction

(Sexual) Vulnerabilities

Spaces

Family

Labor

Resistances

Introduction

This chapter begins with a seemingly simple, yet critical task—to render visible the unique experiences of migration’s most vulnerable populations: not only women, traveling both with and without children, but also LGBTQ individuals. For while all migrants face innumerable dangers along the migratory route through Mexico, it is undeniably women, both transgender and cisgender, and queer compañerxs who find themselves in the most precarious state of all—subjected to painfully intensified forms of the same violence that always seems to plague the non-white, non-male, and/or non-heterosexual, albeit to different degrees.

For vulnerability, as Judith Butler writes, is a constant state of human existence, but one which “becomes highly exacerbated under certain social and political conditions, especially those in which violence is a way of life and the means to secure self-defense are limited.” Migration is one such condition. Following Butler, we can think of vulnerability as the shared, if differently distributed, social condition of being tied to, exposed to, and dependent upon others, as well as on both institutional and social infrastructure. Along the migratory route, violence emerges as the exploitation of vulnerability—a ravaging of bodies that capitalizes, both financially and otherwise, upon the common and specific ways in which each migrant is uniquely dependent upon others during the course of their journey.

As this chapter aims to demonstrate, traveling under certain conditions—for instance, with children or while pregnant—is more common amongst female migrants and renders them particularly vulnerable, whether to assault and injury, fatigue and sickness, or the increased risks and exposure of a slowed down journey north. Moreover, the high prevalence of rape and violence along the migratory route disproportionately affects both women and LGBTQ migrants, who repeatedly become the victims of brutalizing tactics of exploitation, whether in the context of individual assaults or through the structural violence of (sexual) labor.

The aim of this chapter is two-fold: not only to explore the unique challenges that gender and sexuality pose along the migratory route, but also to emphasize the ways in which multiple resistances—whether quotidian, spatial, aesthetic, activist, community-based, sensorial, spiritual, or affective—seem to proliferate endlessly at the very sites where life feels most precarious. For vulnerability does not imply weakness or passivity, but rather, quite the opposite. The individuals whose stories, though inevitably insufficiently rendered by us, animate this section illuminate how resistance can be articulated in unexpected ways. And the only way to begin to understand how these resistances circulate within the overwhelmingly violent context of migration is to proceed with care, listening carefully and finding a being-with—a vulnerability—that is, for once, about something other than violence.

Labor

Next to the shelter’s closed kitchen, there is a semi-concealed corner from which an intense heat emanates, seeming to fill the space with smoke. Here, a group of women—mainly from Hondurans—vigorously knead 120 pounds of dough to make baleadas. In three hours, they must have enough food ready for 300 hungry men, women, and children.

Drenched in sweat, hands covered in a sticky mix of flour, oil, and butter—the compañeras’ arms were sore after hours of working the amorphous mass, trying to turn it into 900 small, perfectly round balls of a precise size. This, however, was only two thirds of the process. Next, the balls had to be made into baleadas,a transformation that to us—three foreign students stopping by the shelter for a little over 24 hours—somehow felt like magic. Attempt after attempt, our baleadaswere far from round. We took 10 times longer than our compañeras and could only seem to produce irregular triangles, asymmetrical hearts, and narrow, stretched-out ovals.

Labor in the cooking spaces of La 72 Hogar is mostly performed by women: young, old, Honduran, Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and for a brief moment, there was the added, awkward presence of an American, a Canadian and a Mexican. This kitchen was also a notably queer space—a site of community for the trans women who make up migration’s most vulnerable population. One woman told us that when they arrived, La 72 had lacked a space for them, the dormitories being divided between (cis) men and women. After speaking with Fray Tomás, who runs the shelter, the trans compañeras transformed the kitchen into an improvised dormitory, which also became their domain: these women undeniably run the kitchen, deciding what to buy and what to cook and managing the work shifts. The kitchen of La 72 is therefore a powerful site of queer sociality, one upon which the rest of the shelter critically depends. It is a place to be together, to cook, to feel safe for a little while, to spend time with other women—some married, some in search of love, some mothers, some widows. Occasionally, several men bring wood or carry some of the heavier pots and pans—but the only constant presence in this space is that of women being together.

When asked if this had always been the case, the women’s faces were revealing: this is how it works. We all have our tasks in the shelter. This is ours. We have teams. We take turns, they seemed to say. Labor, in La 72 as in the rest of the world, is a relationship, a system in which tasks are divided, but also one in which positionality plays an important role in constructing oneself in relation to others.

Labor, as our clear failure in the preparation of baleadas illustrates, is also a skill-set. One woman named Paola told us that she and her mother had a baleada stand back in Honduras, “on Third Avenue.” “The best one in the area,”she argued, as she came over to check that our balls of dough had the right consistency. “I don’t use eggs in my mix. I use a little sugar, though, because it neutralizes the salt,” she continued. Another woman named Osiris intervened: “Well! Eggs make the flour, salt, and water come together in a better manner.” She was our maestra, laughing hysterically every time we came close to achieving a round shape or when our dough began to feel soft and tender.

The knowledge and stories shared in this kitchen offer a quick glimpse into the gendered experiences of labor that play out not only within shelters, but also throughout the process of migration: along the route, in countries of origin, and in those of destination. The notion of “labor migration” was, until recently, mostly associated with men traveling to the United States in search of work—trying to send money to their families who usually remained in their countries of origin.

In past years however, the devastating effects of increasing violence, widespread crime, and deteriorating economic conditions have forced many women and children—some under one year old—to migrate as well. This incorporation of women and children into migratory trajectories is growing steadily, according to both the activist organization Sin Fronteras and the National Institute of Migration in Mexico (INM).

Almost half of those who left their countries in the past years are women—42% according to estimates by the INM. While certain facets of these women’s experiences of migration may be shared along gendered lines, such as traveling with children or being vulnerable sexual assault, there are also profound differences in terms of both expectation and practice along the migratory route that cannot (and should not) be collapsed into a singular “female experience.”

En el camino journalist Ángeles Mariscal explains, Guatemalan women who successfully cross the southern border into Mexico are almost always pushed into domestic service in cities like Tapachula, Chiapas. The working conditions undergone by these women, many of whom are indigenous, are (infamously) well-known in the region. Often working in their employer’s house for more than 12 hours a day, six or seven days a week, they are usually only allowed to eat leftover scraps of food—just enough to survive, while their employers lead luxurious lives, consuming food and other goods seemingly without thinking twice. With little to no protection from labor organizations, these women are almost entirely dependent on informal networks through which employers can exploit their labor, even threatening them with deportation. Isolated from family and friends, these women often find each other in various spaces around the city, such as Miguel Hidalgo park in central Tapachula, where, for short periods of time, they encounter their fellow nationals working under similar conditions and with similar lacks and needs.

Women from El Salvador on the other hand, seem to be invisible, according to Mariscal. Somewhat excluded from the racial schemata that targets many Central American women and places them in particular lines of work, Salvadoran women become visible mostly in the context of labor that others are unwilling to do. Thought of as particularly tough—a quality attributed to their experience through the country’s violent civil war—these women are, in Mariscal’s words, the ones that are “up for anything.”

Unlike their Guatemalan and Salvadoran counterparts, women migrating from Honduras tend to end up working as waitresses in Mexican cantinas, or bars that typically cater to men, in strip clubs, or as escorts and sex workers. In the most extreme cases, women work on the street or in the dark alleyways behind markets and bus stations. According to CNN México, almost 90% of women doing sex work along the southern border are from Central America; as Mariscal elaborates, they are often Honduran specifically. With little to no protection, these women are extremely vulnerable to violence and exploitation.

Not only are women arrested for and criminalized as sex workers, but also as human traffickers. In a supposed effort to combat human trafficking over recent years, Mexican officials have been arresting and imprisoning many women on false charges of managing trafficking networks. These detentions have been denounced by the women themselves as founded on false, coerced accusations and altered testimonies, with various journalists, human rights organizations, and individuals, such as Luis García Villagrán, whose discussion with us is available below, supporting their claims.

Regardless, the multifaceted discrimination against and criminalization of these women—as migrants, sex workers, domestic workers, and alleged traffickers—have placed them in an increasingly precarious situation, as they find themselves exploited and abused by both their employers and by government officials.

What Mariscal’s analysis makes evident is the way in which migrant women’s labor is not only informed by gender, but is also organized by a racial/racist apparatus that categorizes women according to imagined phenotypic characteristics, temperaments, and socio-political histories. This division of labor taps into and perpetuates existing and violent stereotypes about race, gender, and nationality: indigenous Guatemalan women are docile and submissive, Honduran women are promiscuous and have stereotypically beautiful bodies, Salvadoran women have lived through so much violence that they can live through anything. The mechanism that funnels women into these racialized lines of work is complicated, having almost as much to do with their own expectations of what they are supposed to do as it does with what they are forced to do. As Mariscal notes, one Honduran woman explained to him that she knows she’s going to get hassled for sex regardless of what she does, so she decided that she may as well just go work in a cantina right away.

Family

Through our encounters with migrants, we discovered that most were motivated by a powerful desire to protect and care for their families. Many were attempting to escape gang violence or to avoid the gang recruitment of their children; others were working to make enough money to provide healthcare for sick family members; others were trying desperately to reunite with a spouse or child in the United States.

Despite these similar aspirations—common across gendered lines—it was mostly women who were traveling with children. At La 72, we met a woman named Andrea traveling with her two-year-old son, her aunt Magaly, and the latter’s two preteen children. Andrea’s husband had stayed behind in Honduras, but if they managed to cross successfully into the United States, he intended to join them. That part of the plan, though, seemed to hang in the balance. Andrea and Magaly were only at the beginning of their journey, and so kept their expectations in fragile equilibrium: caught between a profound faith in God’s providence and protection and the frequent, qualifying ifs scattered incessantly through their story. “If we cross. If…if…if…”

Traveling with children carries its own unique challenges: one can’t walk too much, or one must walk more slowly, or one must carry them. There are incessant worries about injury and, of course, anxieties about getting them on and off La Bestia, the northbound trains that migrants perilously travel on top of, especially with rambunctious, fidgeting toddlers. These extraordinary concerns pile up atop the usual ones that define parenthood: the health, food, clothing, safety, and happiness of one’s children. Traveling while pregnant entails another set of difficulties—the mother needs more rest, and she must be conscious of any food and water she consumes. Because the conditions under which most people migrate are unlikely to facilitate such precautions, pregnancy becomes risky for both mother and fetus.

Those who leave family members behind, planning to send remissions or eventually bring them over, face different struggles. At Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes, we met Johana, a woman from Nicaragua traveling with her sister Karolina. Johana had left her two daughters, small grandchildren, and elderly parents back home. When asked about her reasons for migrating, she replied that she and Karolina need to make enough money in the United States so that they can pay for two surgical procedures that her grandchildren, both of whom have complicated health issues, urgently need. Deciding to travel without her daughters and grandchildren was a difficult decision for Johana. With tears in her eyes, she explains that when her granddaughter asked if she could take them with her, she said that she couldn’t. She’s not leaving them because she doesn’t love them, she tells us, although it might look like that (of course, to us at least, it doesn’t).

It is precisely because she does love them that she has to leave without them. Family is therefore both that which motivates leaving and that which weighs upon one while traveling. Longing for family—the very people for whom one makes the journey in the first place—can even make one second-guess the decision to migrate. When we asked Magaly whether she had been able to talk to her family back in Honduras, she told us that she had let them know—just once—that she was fine, but that she doesn’t really want to talk to them because it makes her too sad. Andrea, with watery eyes, agreed.

Resistances

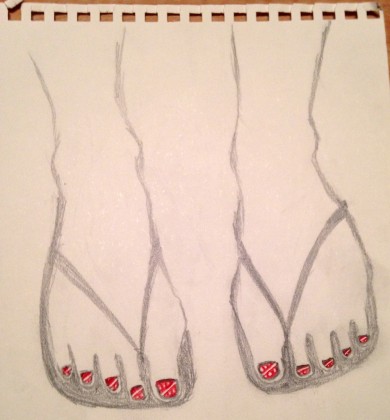

Karolina’s yellow eyes stare at us worriedly as she tells us about the journey thusfar as she heads toward the United States. We are sitting at the Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes in Chahuites, Oaxaca. Karolina and her younger sister Johana arrived at this shelter that same day at five am. Poverty in their home country of Nicaragua is pushing them north, as they struggle to make enough money to care for both their parents and Johana’s grandchildren. The sisters walked for straight 12 hours before arriving at the shelter in Chahuites, and during that time, they were robbed once and tricked out of their bus money. They were wearing flimsy sandals and their feet hurt. Karolina was limping. They still had a four-day walk to Ixtepec in Oaxaca ahead of them. Johana tells us that during this journey they will only sleep for 20-30 minutes at a time “in order to minimize risk.” We take this to mean “in order to avoid being robbed or raped.”

The sisters were not sure where they were going next. They were certain, however, that they would have to walk much farther, that they would likely get robbed or tricked again, and that they might be raped. Both had received contraceptive shots before leaving and both carried condoms with them, just in case. We don’t know where Karolina and Johana are at this moment, but if they did decide to keep going, the journey ahead of them was and possibly remains undoubtedly a perilous one.

The act of migrating might be framed as an act of resistance in and of itself—albeit usually a forced one—against totalizing poverty, violence, and death. But there are also more subtle acts of resistance that evidence humanizing strategies that migrants use. These everyday acts allow for small pauses in the brutal, incessant reality of migration. In the case of the Nicaraguan sisters, this resistance took the form of painting their nails. As one of our group members narrates:

We are at Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes in Chahuites, Oaxaca. I feel awkward, and I don’t know how to begin a conversation with strangers. I want to talk to some of the women beside me, but I feel overwhelmed. What can I possibly say in this situation? Probably not much. And what can a migrant gain from talking with me? I remember Dori Laub and Shoshana Felman’s discussion of the ways in which survivors of trauma often need someone to listen to them—to witness, to help bear the burden—in order to reconstruct and process what they’ve gone through. But if these women don’t want to take the conversation there, maybe I can offer some sort of distraction. Yet, even with this in mind, I don’t know how to start. But then, before I am able to continue with this negotiation of my own anxiety, I see a flash of red on a woman’s toes. This is Johana. She is sitting on a small bench. She looks tired. She rubs her feet and calves intermittently. I gather that she must have been walking a lot. Her feet and muscles must hurt. But her feet, rather than looking worn and blistered, are perfectly polished. Her toenails are bright red with intricate white details. “I really like your nails,” I tell her. She looks at them and smiles. “Did you paint them here?” I ask. She shakes her head. She tells me that she was in another shelter before, and some women brought nail polishes and offered to paint them. For a moment, her feet aren’t only a source of pain, but also a temporary bodily reminder of a moment of kindness, sharing, and care. Because the act of painting nails—especially with such complicated details—requires gentleness, precision, bodily contact.

In the context of migration, that which might appear trivial operates not only as a distraction from violence and hardship, but also as a strategy of resistance, pushing back against the depersonalization and dehumanization that migrants are subjected to. Far more than a marker of femininity or a bodily adornment for the aesthetic appreciation of others, nail painting is a reaffirmation of oneself as a subject with agency over one’s body—a body constantly under siege and threatened by rape along the migratory route. We found similar acts of resistance as we sat with a group of women who were learning how to knit together at La 72.

The knitting was what allowed me to speak to that group of women. As an artisan myself, weaving mandalas and offering workshops, I saw this as a potential entry point into a conversation with them. I approached the group and asked if I could sit with them. They said yes. I asked what they were knitting, and our conversation began. I met Bessy and Misdelis. Bessy is a young woman from Honduras who had been in the shelter for a couple of weeks. She was excited about making the baleadoras that were to be served for dinner that evening. We practiced our English together. We did not speak about her migration story. Misdelis is a middle-aged Cuban woman. She spoke to me about the gay community of La 72: how they make crafts during the day and sell them at night to make some money. We didn’t speak about her migration story, either. But that I was able to socialize with them like this says something important about what happens when they get together to knit in groups: they can do it on their own, and they do.

Cultural-artistic activities like knitting can often allow groups of people like these women to build community through bonds of solidarity, even if only temporarily. Alliances between migrants are not uncommon, but they happen in very specific moments—helping each other get on the train, warning one another about approaching danger, passing on information about migration routes—and can be easily broken. Paths diverge, and the constant threat of violence and death destabilizes relationships. Creating community offers a resistance against the violent effects of migration—fleeting moments of crucial interrelationality formed amongst a mobile, transient, and ever-changing group of people.

Furthermore, knitting together, following Ann Cvetkovich, can be understood as a spiritual-affective process of making, during which agency is allowed to take on a form other than the application of one’s will.

For while—and in fact, precisely because–knitting together is not an intentional act of resistance, it allows us to think resistance and agency differently. Recognizing this is crucial, as it forces us to acknowledge the suffering, sacrifices, and actions of resistors—in this case, migrants.

Migrants also engage in more explicit acts of resistance, often in the form of organized actions. Take, for example, the hunger strike planned by 36 migrant women, both in and out of prison, with the help of human rights defender Luis García Villagrán.

With this action, these women are protesting the false accusations of human trafficking levied against them by Mexican officials—a plight that has become all too common amongst Honduran and Salvadoran women in cities along the migration route like Tapachula.

Other types of organized actions—even if more informal—should also be acknowledged as forms of resistance. The appropriation of the kitchen space at La 72 by trans women and queer men as a space in which they cook, sleep, congregate, chat, and hang-out is a telling example. Not only have these marginalized individuals created a community that resists the usual instability of bonds amongst migrants, but they have also imagined—and thus created—a queer, safe space outside of the usual gendered binary that divides the shelter’s sleeping quarters and the world outside of them.

We encountered many examples of resistance, each differing from the other in terms of (in)visibility, degree of organization, and level of intentionality. Those described here relate specifically to the unique lived experiences of both migrant women and LGBTQ folks who, through these practices, contest the violent, often hetero-patriarchal contexts in which they are forced to subsist. It is crucial to acknowledge these acts of resistance, even if they are unintentional, opaque, or feel strange to us. For such an acknowledgement might open up the possibility of recognition, and perhaps, eventually and in some way, a kind of justice.

(Sexual) Vulnerabilities

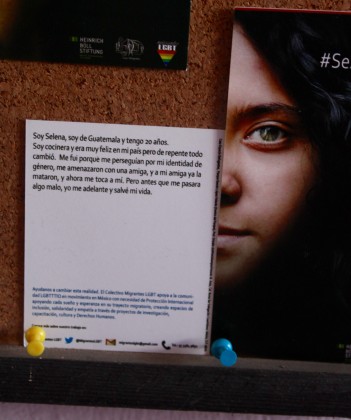

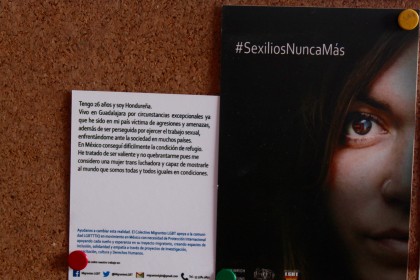

Abused, silenced, and often invisibilized, many women and LGBTQ individuals are pushed to migrate in large part because of the violent gendered and/or sexed discrimination they face in their countries of origin, entering into what Puerto Rican sociologist Manolo Guzmán has termed sexilio. Many quickly realize however, that sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and machismo flood across national borders with disconcerting ease. The migratory route is never safe, but it is even less safe for some.

On our trip through southern Mexico, we learned of a “rape tree” near the Centro de Ayudo Humanitaria a Migrantes. The director of the shelter told us that this tree’s base was cluttered with improvised mattresses and that women’s underwear hung from its branches like trophies. And it was not the only one of its kind—there were others scattered throughout the community. With most women understanding rape, particularly by local gang members, as an inevitable part of migration, many preemptively take birth control and carry condoms to at least prevent pregnancy. In the shelters, dormitories are importantly gender-segregated. But rape is also a real risk for men traveling along the migratory route. In Chahuites, different migrants and human rights workers emphasized this to us: It happens to men, too. While largely unreported and unacknowledged, male-on-male rape does occur along the increasingly militarized and violent migratory route and is often understood as a technology of humiliation. The disavowal of male-on-male abuse—connected directly to its use as an instrument of shaming—is a powerful indicator of the implicit homophobia that has helped shape the discourse of sexual vulnerability. We seem to lack a language for it. Thus, while women, and particularly trans women, are disproportionately affected by sexual violence along the migratory route, men also find themselves vulnerable to those who would prey upon them, though engrained homophobia renders it differently invisible and them differently silent.

Spaces

What does it mean to create a collective space where the dispossessed can feel welcome and safe? And how do these spaces make gender and sexuality (in)visible within contexts strongly shaped by gendered social norms of behavior and appearance? Migration excludes no one: single women, siblings, entire families, transgender folks, and people with diverse sexualities all migrate. Along the migratory route, how can a space simulate an environment of transformation, solidarity, and resistance—a way of providing rest and strength for what lies ahead? Following Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, this section asks how migrants—situated in particular spaces—use daily practices to subvert the rituals and representations socially imposed upon them. This section also tries to think (in)visibility in relation to Wendy Brown’s notion of the “spectacle of the wall.” The spaces explored here—FOMMA (FOrtaleza de la Mujer MAya), La 72, Refugio Los 3 Angeles, and Oventik (a Zapatista caracol)—are made visible, paradoxically, precisely because of their walls: walls in the form of an ideology stating difference, as well as material walls creating physical seperation.

But these walls also allow for invisibility from the outside world, due to their autonomous construction of a (safe) space within. This seperates them from larger spectacle of capitalist-patriarchal society. In this sense, we might conceive of the construction of walls (whether ideological or physical) that function in a way differently from their usual association with exclusion and a phobia of the Other. Instead, these walls delineate a space for protection, non-violence, and self-creation.

Over the course of our time in southern Mexico, we encountered women and LGBTQ migrants involved in feminist theatre, passing through migrant shelters, and residing in autonomous Zapatista communities. Some of these spaces felt charged with the kinds of social expectations that perpetuate stereotypes and foment gender violence. Others were more subversive, generating gendered spaces of strength, conscious positionality and security. And others worked to create spaces apart for refugee families, women, and LGBTQ folks. This section focuses on the latter two.

FOMMA (FOrtaleza de la Mujer MAya)

Five women collectively weave together the story of a family fragmented by migration. The stage is in the middle of the tiled, covered courtyard that is FOMMA’s main space. Masks and simple props differentiate scenes and characters.

Throughout the play, audience members shed tears, erupt in laughter, and share solemn silence. After the play is over, the playwrights and actresses share their stories of how each became involved with FOMMA. Several describe theater as a therapeutic space in which to share personal struggles, suggest solutions, and together—with the audience and other playwrights—begin to transform themselves as well as their communities. Other women had no previous experience with theater, but found themselves intrigued by its capacity for expressivity. Over the years, FOMMA has persisted, not as a fixed place but as a transient one, visiting communities near and far and performing plays for audience members who can often personally relate to the stories these women tell.

In this way, FOMMA’s plays not only allow the playwright-actresses to engage in therapeutic processes of self-transformation, but also importantly invite audience members to engage with the material, encouraging them to make space in their communities for other ways of being in the world.

The Autonomous Zapatista Territory of Oventik exemplifies and enacts daily the power of a place apart. Guarded by a locked gate and two sentries, all traffic is regulated and recorded. Only those ideologically aligned with the Zapatistas are welcome. Otherwise, the wall becomes opaque, invisibilizing the community and protecting it from the outside gaze. The Zapatistas have, against all odds, created an autonomous community that decides when, how, and to whom it is (in)visible. Rejecting the “bad (Mexican) government,” they work tirelessly to resist oppression and coercion. Moreover, they have creatively reimagined their own social organization so that it benefits the community. This practice of resistance has produced a “good government” that ensures access to education, healthcare, land, self-government, liberty, justice, and gender equality. Zapatistas have made possible those services that the Mexican government promises but never delivers, in this way ensuring their own well-being, autonomy, and continued survival.

During our visit to Oventik, we witnessed the “cultural presentations” of Zapatista students. We saw two women dancing in the middle of a basketball court, feet slapping the large puddles forming in the steadily falling rain. Heads held high, handkerchiefs wrapped firmly around their faces, covering their nose and mouth, the women make palpable the effort of the Zapatistas— to create a space that instills the knowledge that each individual is a subject of rights. Through both voice and movement, the Zapatistas provide a public platform for women to speak. During a series of speeches inaugurating the twelfth anniversary of the caracol that evening, one woman spoke the discourse, first given in Spanish, in Tsotsil. But she was not just translating. She was giving a conscientious re-reading and adaptive representation in and through both the language and cultural expression of the Tsotsil community. Through both embodied movement and verbal expression then, Zapatista women articulate their rights to speak and to be heard.

La 72

It’s not that we don’t let the men cook…but if we want to eat well, the women have to be in the kitchen.

Osiris, a woman staying at La 72

Music blasts from the tiny speaker. Hips move, laughter erupts. Some hands measure out ingredients while others mix and knead dough. The adept pinching and rolling of dough creates small balls that will rise. “Girls, some people will be without baleadas if you make them that big! Smaller!” says Osiris. Then there is the expert stretching and slapping of dough from one palm to the next to form perfectly round baleadas. The women lay them out on the griddle and, with sweat trickling down faces, flip them over and removed when they are cooked. Women preside over this space, with their culinary knowledge, their physical presence, their harmonized voices, and their swaying hips creating a space that is very much theirs.

In another section of the kitchen—by no means separate—hands skillfully wield knives, finely chopping onions, splitting avocados, and carving out bruised chilies and limes. In this queer space, where trans women, cis women, and gay men have formed community, donated, almost-rotten vegetables are salvaged. A migrant named Josué Roberto Sevilla Caballero tells us about inclusivity of La 72. His words are reminiscent of Fray Tomás’s talk earlier, in which he laid out the mission of the shelter: “The idea is to give life.” Fray Tomás stresses that giving life means supporting the way in which each individual chooses to live—”we walk with them.” Perhaps because of Josué’s words, a new arrival at the shelter joins us at the table. He begins testing the water, offering his take on the inclusion of LGBTQ migrants. “Before I had long hair—longer than yours—and my friends would make fun of me and ask me why I had such long hair. I told them: for no reason, because I liked it. Sometimes they would call me gay and things like that, but it didn’t bother me because I knew I wasn’t like that…I mean, don’t think that I have an issue with gays. It’s not like that at all—I mean, every person should do what they want to do. It’s just that I wasn’t gay.” As the discussion continues in this vein, through the telling of stories encouraging openness, it becomes clear that those gathered around that table are beginning to let down their own (invisible) walls. Soon after, the new arrival pulled his chair very close to us and whispered that he was gay and that he had dressed as a woman for several months. If he had expected drama, there was none. Others encouraged him to be true himself: “If you want to dress up, do it,” says Josué. “This place is safe. Nothing will happen to you here. Be who you want to be,” says another gay man. This queer, radically inclusive kitchen offers one powerful example of how spaces within La 72 can, at least temporarily, give life.

Refugio Los 3 Angeles

With only 100 pesos, Doña Olga had a vision. She broke new ground when she began constructing walls in order to house, care for, rehabilitate, and provide refuge for migrants wounded by La Bestia or along other parts of the route. Today, her shelter built, she turns away no one. In fact, her most recent project provides temporary “apartment-style” housing for migrants traveling with their families and awaiting the state’s decision on their refugee status. One resident from El Salvador told us that it was a rare oasis in tumultuous landscape. This was made clear by the three young girls, 7 to 12 years old, who were “playing house” in the communal wash station located at the back of Refugio Los 3 Angeles. With thin wooden planks and small plastic toys, they traced their own migratory map. Each miniature structure represented a country, with El Salvador placed farthest from the shelter. These young migrants were not just playing an imaginary game: they were living it. Fully aware that their playmates were temporary—families come and go—the girls narrated their journeys, making the toys on the map come to life. They laughed and poked fun at each other as they placed themselves firmly within their own maps. This space, made possible by Doña Olga’s commitment to accommodating migrants as socio-political environments change, makes a moment of childhood possible. Even if it is only temporary, even if these young girls can’t help but play imaginary games based on their brutal realities.

de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven F. Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press, Brown, Wendy. 2010. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty. New York: Zone Books, Guzmán, Manolo. 1997. "'Pa la Escuelita con mucho cuidao y por la orillita': A Journey Through the Contested Terrains of the Nation and Sexual Orientation" Puerto Rican Jam: Rethinking Colonialism and Nationalism. Edited by Frances Negrón Muntaner, and Ramón Grosfoguel. 209-228. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, Stemple, Lara. 2015. "Male Rape and Human Rights." "Male Rape and Human Rights." Hastings Law Journal 60. 605-646. Hollander, Joceleyn A., and RachelL. Einwohner. 2004. "Conceptualizing Resistance." "Conceptualizing Resistance." Sociological Forum 4. no. 19: 533-554. Laub, Dori, and Shoshana Felman. 1992. Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature. New York: Routledge, Cvetkovich, Ann. 2012. Depression: A Public Feeling. Durham and London: Duke University Press, Mariscal, Ángeles. 2013. "La industria sexual: el camino de las migrantes centroamericanas en México." CNN México, 8 Mar 2013. http://mexico.cnn.com/nacional/2013/03/08/la-industria-sexual-el-camino-de-las-migrantes-centroamericanas-en-mexico. Mariscal, Ángeles. 2014. "Mujeres migrantes, atrapados en une frontera imaginaria." En el camino, 3 Jun 2014. http://enelcamino.periodistasdeapie.org.mx/ruta/mujeres-frontera/. Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso,