Section Menu

The Difficulty of Mapping Migration

Maps, Territory, and Representation

Legends and Encounters

Migrant Bodies: Territories of Rebellion

What Gets Lost in the Map?

The Right to Have a Map

How Do We Position Ourselves in the Map?

The Difficulty of Mapping Migration

While migration is certainly not random, it is still very difficult to map. Rather than identify a starting date of mass migration across the Americas, therefore, Ruben Figueroa, human rights defender for Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano, rephrases the question to be, “What are the moments in which the migratory flow intensifies?”

These moments are various, yet all very similar in that they include the flow of more than just people. Indeed, the migratory flow is often a reaction to more insidious flows: those of arms and armies, as well as drugs and transnational companies.

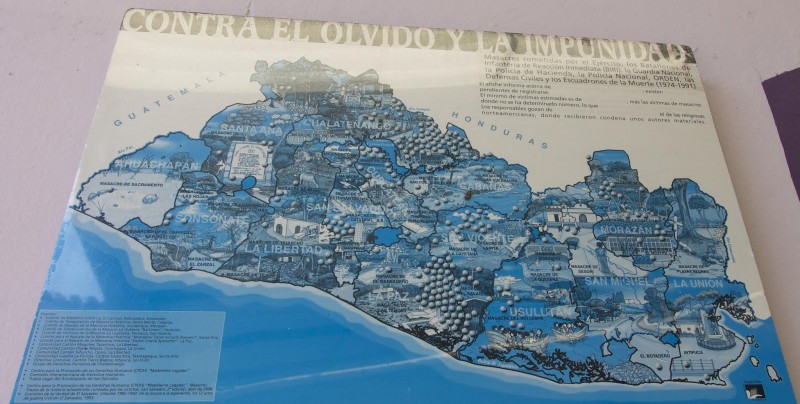

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, for example, the United States trained and financed brutal counter-insurgent campaigns across Central America, inadvertently forcing many Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Nicaraguans into exile. We could call this the first moment of intensified migration within recent history. It overlaps, however, with the implementation of free trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), and the Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA), which continue to exacerbate unemployment, land dispossession, and illicit markets across Mexico, Central America, Colombia, and beyond. This second moment began in 1994 and has yet to end. The mass deportation of US-based Central American gang members starting around 1995, Hurricane Mitch in 1998, and Hurricane Stan in 2005 were also overlapping moments of increased violence, poverty, and thus migration northward. A third moment could be marked by Mexico’s formal declaration of a so-called “drug war” in 2006, which effectively expanded drug trade and organized crime in a way that not only caused more migration, but also made such migration even more perilous than it already was.

While the migratory flow clearly rises and falls in relation to other political, economic, environmental, and social movements, Figueroa distinguishes it as a flow that always moves in the same direction: “It goes there (up, north) always…but it’s also very vulnerable.” In just the last half decade, for example, traditional migratory routes have been continually diverted by tightened security regulations within Mexico, largely due to the influence of a post-9/11 United States. The more migratory checkpoints, detention centers, and laws against train travel that Mexico implements, the farther migrants must travel on foot and across uncharted territory that basically belongs to organized crime groups such as Los Zetas. Though Mexico passed its first migration law in 2011 and Plan Frontera Sur in 2014, both with the ostensible purpose of ending government corruption and decriminalizing migrants in order to grant them safer passage, the overwhelming result has been more human rights abuses and more deportations.

Even such deportations, however, do not stop the flow of migration northward. Rather, they turn the migratory flow into a highly circuitous one. While recent statistics indicate that fewer migrants are currently reaching the Mexico-US border, therefore, it is important to remember that no fewer people are crossing from Central America into Mexico.

Many people currently migrating northward are doing so for their third, fourth, or even eighth time. They will not stop. For as long as colonial, imperial, and neoliberal practices continue to inundate these people in ways that dispossess them of their safety and their very citizenship, let alone their livelihood, they will continue to improvise on the most popular escape route there is: a route that is different for everyone, yet universally without end. As such, mapping the trajectory of migration comes down to tracing multi-directional flows: not only of people, but also of the factors that cause those people to migrate in the first place.

Maps, Territory, and Representation

In his short story “On Exactitude in Science,” Jorge Luis Borges imagines a kingdom in which a widely-held obsession with exactitude leads to the creation of a map that replicates the actual scale of the kingdom’s territory. However, it rapidly becomes obsolete, as it finally ends up merging point for point with the land it seeks to map. The inhabitants of this kingdom forget its existence, and life continues to grow from the ruins of this ambitious map. The map itself, although useless for its intended scientific and political uses, gives birth to new geographical formations within the same territory it initially tried to map. The map becomes part of the territory and not simply its representation.

There are certainly some aspects of this obsession at play in the formation of borders and nation states, and they are particularly intensified in the ways in which the Mexican government, with the financial, military, and logistic support of the United States, tries to control its southern border. The role of maps in the formation of our current geopolitical context cannot be denied, but it also cannot be considered simply from the perspective of the powers producing official maps. As a collective, we were surprised by the ways in which migrants, shelter volunteers, and activists practice and share maps in ways that are highly narrative. In this practice we found a form of transmission that is not simply a visual representation, but also the embodiment of a whole system of affects that gets spread through the territory. In opposition to the stability of visual maps, narrative maps are performed every time they are narrated; therefore, they must be considered as a form of resistance to the constant changes the migratory route undertakes.

See the Interviews page for a translated transcript of this video.

The narrative map responds faster to changes in migratory routes, thus enabling migrants to quickly incorporate these changes and many other aspects that cannot be so easily included in printed maps. In opposition to official maps, we find what we came to call “narrative mapping,” which is a form of mapping that relies less on the visual and more on the narration of events that can happen to a migrant when he or she undertakes the migratory path through Mexico.

Plan Frontera Sur can be considered as a form of mapping that, in its blurriness, is quickly transforming the maps charting the Mexican southern border and the social, political, and economic relations in this region. These forms of mapping alter the visual representation of the territory, but they also alter the concrete relationships that take place within that territory. However, the formation of official maps is contested and resisted by the movement of bodies, subjectivities, stories, music, and affects that cannot be included in them. Even more, the resistance to be mapped speaks of the inexactitude inherent in mapping techniques and at the same time reveals the cracks that every system of control has.

Legends and Encounters

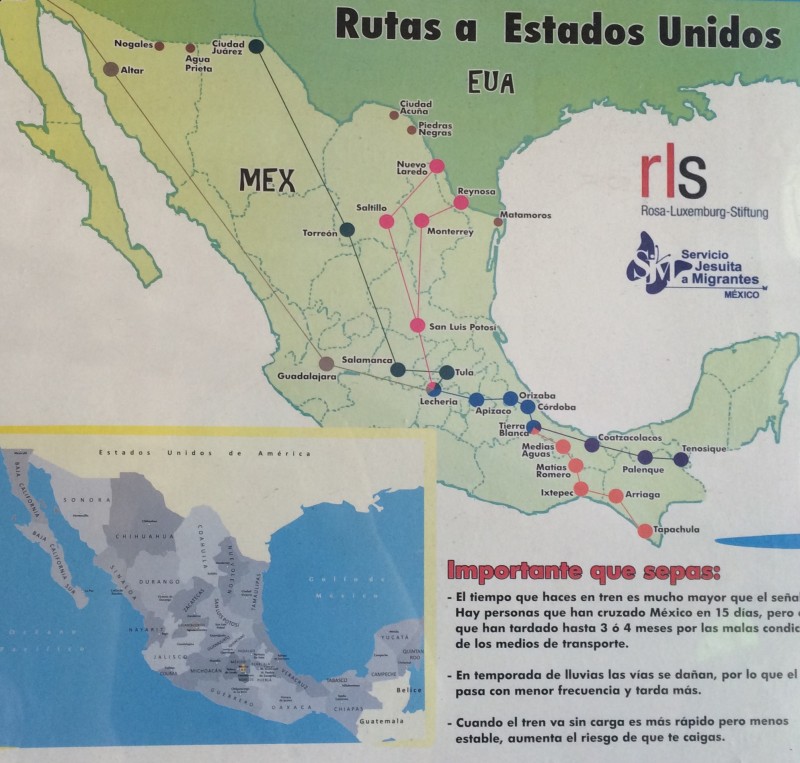

Maps are conventionally perceived as illustrating the physical features of an area, as a spatial representation of terrain, or as the tracing and documentation of an area traversed. In the case of migration, the mapping of routes seems to be a significant emblem of a migrant’s journey. Indeed, each shelter, human rights organization, and institution that we visited displays route maps. The maps became a source of our group’s fascination, as if they displayed clandestine details of where migrants have gone or will go—of the various possibilities when fleeing to El Norte.

A map implies traces that are documentable, preservable, repeatable, uniform, but the reality is that such a journey does not exist. Though “official maps” take on institutional, economic, and political significance, when speaking with those who have been on the trail, it becomes evident that there is nothing clear, direct, or delineated about the path. So while migrants might follow routes, look at a shelter map, or try to locate various markers, the only geographical points of significance are where one begins and where one ends—all other movement is generated by encounters.

The circumstances and structure surrounding migration transform daily and thus, no two maps or journeys are similar. Even those who have been repeatedly deported and forced to replicate their journey are met with an evolving sociopolitical terrain that necessitates constant negotiations and shifts. As migrants have increasingly been displaced off trains and onto foot, the precariousness of walking through the rural countryside constantly forces migrants to alternative paths. The logistics of travel are often indeterminable: nobody knows what time La Bestia (a term for the trains heading north across the country) will depart or whether they will need to abandon a route due to bandits, narcos, or gangs. It is within the encounters, the derailments, and the evasions that we find disjointed, unmappable routes.

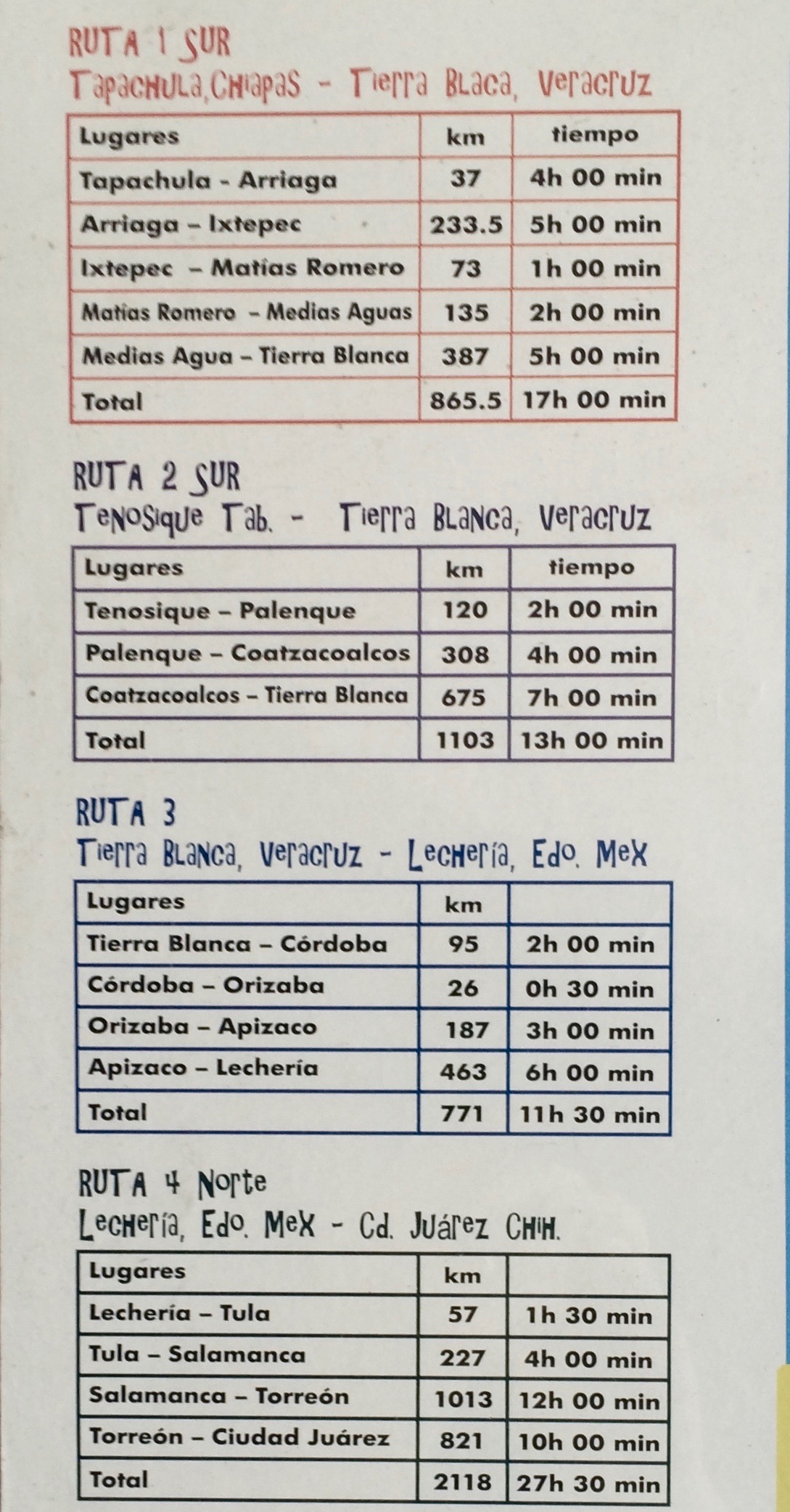

Many of the shelter maps—such as this one from Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías de Córdova—present the routes simplistically, including paths to follow, distance to travel, and approximate time estimations from point to point.

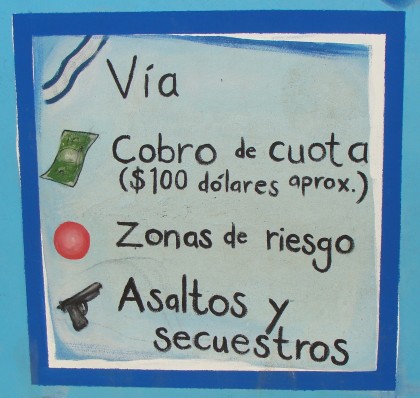

Perhaps the most striking representation of a map was the mural painted at La 72 Hogar, which represented not only the routes, but also characteristics of various locales that might prompt migrants to seek out certain locations or to avoid them.

The legends scattered around the periphery of the map included visual markers for features such as migrant shelters, food and drink, areas of extortion, risky zones, as well as areas of robbing and kidnapping. Despite its being a beautiful and useful resource, we wondered how accurate such a representation is, given the constantly shifting circumstances that reposition migration and violent crime.

While these maps certainly serve as crucial outlines for the treacherous journey through Mexico, speaking with migrants and hearing their narratives suggested how fluid maps become on the long, dangerous, and perpetually evolving journey. These shared narratives stood in stark contrast to the concrete maps tacked or painted on walls. When recollecting the journey, for example, very few migrants mapped out their journey using a geographical model; rather than referencing specific places, people recounted events, transactions, fears, desires, and relationships.

When we spoke with Josue, a sixteen-year-old boy traveling from Honduras, he told his narrative as a short series of encounters, naming only two geographical regions. One was Guatemala, the place where he contacted his mother to retroactively inform her of his departure and where he and his comrades were picked up by police and interrogated for three hours before they were ultimately released. The other was a point just beyond the southern Mexican border, where he and these same companions were scared away from an abandoned house that they suspected was haunted. Both of these locales were unspecific, only memorable as imprints of encounters and experiences that directly influenced his next move.

Josue’s series of fragmented recollections privileges a narrative map over a geographical representation: location only becomes significant enough to be archived on his “map” when such a place is linked to a poignant occurrence. For Josue, a phone call to his mother, a police encounter, and a haunted ranch make up his path from his aunt’s home in Honduras to La 72 in Tenosique, Tabasco.

Asking migrants where they have been and what they have done thus often leads to a long, winding, discursive recollection of memories and experiences, creating maps that are patchwork quilts of happenings. Such a map is performative, illustrating that migration is not documentable chronologically, or even geographically. Rather, it is experienced, embodied, and archived in memories of lived encounters.

Migrant Bodies: Territories of Rebellion

As with all movement, migration implies duration. Experiencing something over a duration implies being able to endure, to resist. As a durational performance–since it is happening–the body, in its endurance, becomes a territory of rebellion.

Nicaraguans, Salvadorians, Guatemalans, Hondurans, migrants from different countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Cubans, and Maghreb all experience the process of forced geographical displacement, being forced to leave their countries of origin to embark on new paths, and thus tracing an alternate map to that of geopolitically established cartography. But the undertaken task manifests itself ritually as “twice-behaved behavior” in a variety of survival techniques that involve highly embodied practices, many of which are also social practices. Migrants restore, manipulate, and transform their bodies in order to keep their lives as the unique equipment that they can carry with them when journeying to the United States, while dealing with the violences of extortion, sexual abuse, drug cartels, and nature itself.

There is a certain ritual while walking this route, evident in the repetitive yet ever-changing patterns of behavior that comprise it. According to multiple migrant interviewees, for example, “when the night falls and we have to walk by the highway, we hide in the woods and keep from looking at car lights: your eyes can actually reflect the light, like those of an animal, and that’s how you get caught,” said a Guatemalan young woman interviewed at La 72.

“When we see La Migra we run and hide in the thorny bushes. La Migra won’t walk into those. They don’t like thorny bushes. For me, the migratory route is like a game,” explained Yahaira, a migrant woman in the Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes.

“I’ve been deported three times from Mexico to Guatemala. For me, migrating is really easy. Since I am mute and deaf, taking a bus is not an option for me: I have to follow the train’s route–La Bestia. That’s my only alternative to get to the United States. Since I can’t hear, whenever I see people running, I also run: that’s what tells me the train is close. If they run, I run. If they hide, I hide. My two brothers and my girlfriend are already there,” said Víctor, a 24-year-old Guatemalan man staying at La 72.

This is how bodily practices and social praxis trace this alternative migratory route in which, alongside the sharing of survival experiences and techniques, other modes of socialization and cultural transfer take place. Side by side with música banda (or bandera), perhaps the music most popular among migrants for its shared prevalence in Central America and Mexico, we can also listen to part of the Guatemalan Garifuna tradition, which appears in the music many Guatemalan migrants listen to while in the migratory route. “Dance and music are within me. I carry them wherever I go,” said a young Guatemalan girl interviewed at Centro de Ayuda Humanitaria a Migrantes.

Alexander, a young man from Guatemala, said, “for us, the marimba is a national symbol, which is deeply respected by all of us in Guatemala and, thank God, in Mexico the marimba is played in Mexico City, Jalisco, Oaxaca, Monterrey, Veracruz, and even around the Tabasco area you can actually listen to it. It is a very beautiful Guatemalan instrument, and I take pride in what it represents.”

However, and in spite of such statements, the notion of identity, as linked to a nation, is also blurred by that of identity as invisibility. Being invisible in order to survive is also part of the identity built into durational migration and displacement. Migrants undergo processes not only of deterritorialization, but also of disidentification with their own culture: a visible display of their own culture implies becoming visible in the migratory route, which is very risky. The migrant’s daily life thus becomes a collection of dynamic processes and, as such, an ever-changing map.

For a migrating body, home is nothing but the physicality of the body itself: home becomes body and, thus, it becomes resistance, just as a wall resists the environment. For in movement, as Mary Louise Pratt reminds us, “displacements, voluntary, involuntary, or anywhere between, amount to a significant shift in human geography, in the way human beings are organized across the planet[…] A growing body of contemporary indigenous thought makes a powerful challenge to mobility as a figure for freedom and knowledge.”

What Gets Lost in the Map?

Ayten Gündoğdu observes that the term “migrant” can mistakenly denote “a misleading sense of easy, unimpeded mobility across borders,” and hence negates ideas of dispossession and statelessness. Indeed, the migrants’ journey is far from being unhindered; their map is a map of illegality, where physical presence in certain territories often entails discrimination, abuse, and risks of detention and deportation. As soon as they embark on their journey, the migrants enter a space of rightlessness. The normalization of migrant illegality delimits the rights of the migrants who, in order to resist their dehumanization, either renounce their rights, or call for their right to have a map of their own: a map that is ungraspable to the state, or even to us, a map that is marked by their own experiences and histories. Even though migrants crossing the Mexico-Guatemala border are welcomed with a sign reading: “in your journey through Chiapas, you have rights,” rights are not always protected on their journey; they somehow get lost in the map, often arbitrarily. Migrants thus become non-citizens: they are the innumerable (dead) bodies put on display for the staging of state authority

While migrants fit into Hannah Arendt’s definition of “statelessness” as non-citizens in a state of precarity and vulnerability, they are not excluded from the state. The state uses them, needs them in many ways, and constantly regulates maps in order to maintain the exclusionary inclusion of migrants, to use Nicholas De Genova’s terms. Paradoxically enough, to resist such dehumanization, the “rightless” hide behind masks, or performances that conceal their “humanity,” such as the violent protest method of lip-sewing. It seems that the only act of mapping that migrants can enact is on their bodies. Indeed, transgressing the official geographical map often takes the form of a bodily distortion, be it symbolic or literal. One obvious example is hiding from La Migra, or the migration authorities, as many migrants proudly recount, or evading and managing the numerous, regular corporeal sufferings involved in crossing Mexico.

The migrants are, however, subjected to a legal system that seeks to manage their bodies and to populate the map with disposable and less disposable bodies. The migratory routes are not without peril. Migrants risk losing and, indeed, often do lose their mobility in different ways, such as amputation or even death caused by riding atop the train. Many migrants we spoke to have been waiting for months in shelters for temporary visas in order to carry on with their journeys, and “realize their dreams,” as Alexander, a Guatemalan migrant and journalist told us.

At La 72, Adi Jared, a 28-year-old Honduran migrant indignantly stated: “Why wouldn’t I be able to go wherever I want? Why do some people have the right to move and others don’t? Why are some travellers, or expats, and other ‘illegals’?”

The Right to Have a Map

In the age of rights, migrants claim the right to map their stories, their experiences, to refuse the attempts at making them invisible. Alexander, who is waiting for a Mexican visa in La 72, is determined to write a book about Guatemalans’ journeys, the lack of economic opportunities in Guatemala, and the racism Central Americans experience in Mexico and the United States. Another example of a desire to have a different map is the Transborder Immigrant Tool, a device that redraws the map, adding safe places for dehydrated migrants in order to guide them to access to water without putting them in peril.

In any case, the right to have a map could also mean the right to not migrate, or “el derecho de no migrar,” as articulated by the Mixtecos. The right to have a map is a resistance to illegality that aims at including migrants not as subordinated subjects, but as individuals with various stories, traumas, and experiences of mobility. If obscenity as explained by De Genova is constructed through “selective exposure,” resistance requires the exposure of difference, of different accounts of mobility: both voluntary and forced ones.

For it is precisely human rights that get lost on more official migratory maps. Throughout their journeys, therefore, migrants negotiate temporary points of safety. Their voices are not always heard. They are speechless. Some of them do not even want to tell their stories. Yet, by struggling to keep their bodies in forward motion, they all effectively shout their rights to have their own maps.

How Do We Position Ourselves in the Map?

Where can we place our photos, our bodies in the map? Our photos, interviews, writings are just a beginning of the emergence of a new map, a map that would account for different histories of struggle and suffering, but also of dreams, cultures, and human encounters. The photo of a shirt taken at La 72, resists the exclusion of the migrants by bringing them into visibility. The shirt functions as a punctum, which allows us to recognize the plurality of the scene: to recognize that migrants do not only inhabit transient spaces such as the border, or the shelter, but also live and participate in the world we live in, and it is our responsibility to acknowledge our role, our (privileged) position in the map.

Weisbrot, Mark. "“Did NAFTA help Mexico? An Assessment After 20 Years.”." Center for Economic and Policy Research, Accessed http://www.cepr.net/documents/nafta-20-years-2014-02.pdf. Schechner, Richard. 1985. Between Theater and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, Borges, Jorge Luis. 1946. "On Exactitude in Science" Collected Fictions. Translated by Andrew Hurley. 325. New York: Penguin Books, Gündoğdu, Ayten. 2015. Rightlessness in the Age of Rights: Hannah Arendt and the Struggle of Contemporary Migrants. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Pratt, Mary Louise. 2016. "Mobility and the Politics of Belonging: Indigenous Experiments in Creative Citizenship" Resistant Strategies. Edited by Marcos Steuernagel, and Diana Taylor. New York: HemiPress, http://scalar.usc.edu/works/resistant-strategies/mobility-and-the-politics-of-belonging-indigenous-experiments-in-creative-citizenship. Arendt, Hannah. 1973. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Orlando: Hartcourt Brace & Company, Magaña, Rocío. 2011. "Deadly Displays of Border Politics" Companion to the Anthropology of the Body and Embodiment. Edited by Frances E. Mascia-Less. 157-171. Malden, MA and Oxford: Blackwell-Wiley, De Genova, Nicholas. 2013. "Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion." "Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion." Ethnic and Racial Studies 37. no. 7: 1180-1198.